Impatient to leave because of circulating rumors of high-ranking commissions in the Confederate Army, Sibley asked for “the authority to leave this Dept. immediately.”

When May 31 arrived and he still had not heard anything, he took seven days’ leave of absence, bid his command goodbye, and left Fort Union on the next stage. He accepted an appointment to colonel in the Confederate army. By June, 1861, Sibley had been promoted to brigadier general.

One of the reasons Brig. Gen. Henry H. Sibley was so wrong about New Mexico's ability to sustain his army was a matter of timing. Since outfitting and training his troops took far longer than expected, Sibley's force didn’t begin the 600-mile march across Texas until November. The landscape of West Texas provided very little grass and other forage for the Army's horses and mules, and there was so little water that Sibley's line of march spaced itself so that each regiment was a full day behind the next, allowing the springs to recover somewhat between regiments. Still, the going was rough and the army began losing hoof stock.

After the war, William Lott Davidson, a 24-year old private in Company A of the 5th Texas, recalled that “‘Chill November’s surly blast’ came down upon us as we camped upon the Nueces. There was no timber to shield us and the wind swept at us, and the boys on guard at night must have had a hard time pacing their beats on the cold frozen ground. We were tasting the bitter delights and mournful realities of a soldier’s life. We are now for the first time beginning to find out that we are engaged in no child’s play.”

Blizzards, combined with too little food and forage led to illness among both men and beast. Measles and pneumonia ran rampant through the troops.

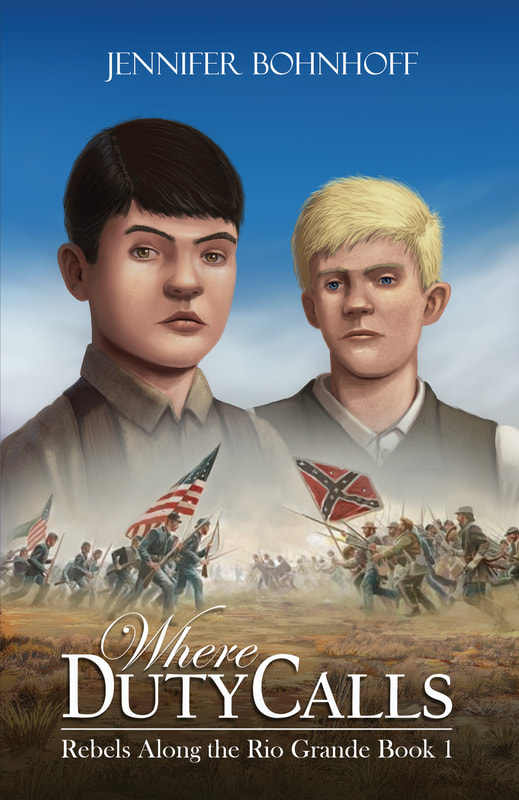

map by Matt Bohnhoff, from Where Duty Calls

map by Matt Bohnhoff, from Where Duty Calls The old western saying that “whiskey is for drinking, but water is for fighting” proved true. The Battle of Valverde occured when the Confederate Army finally returned to the river on the other side of Contadora Mesa and found their access to water blocked by Union troops.

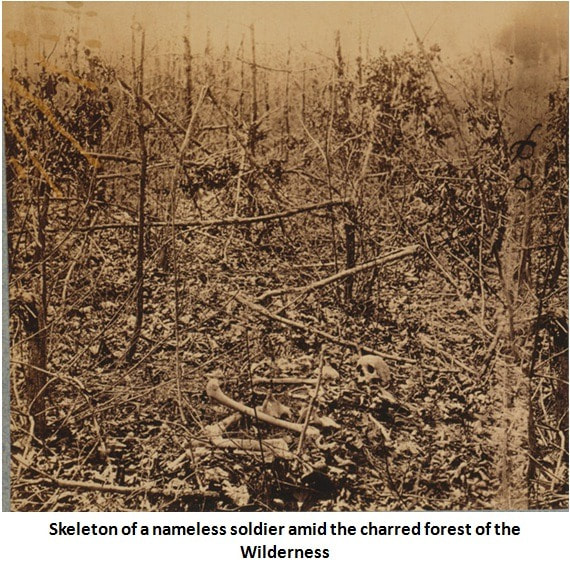

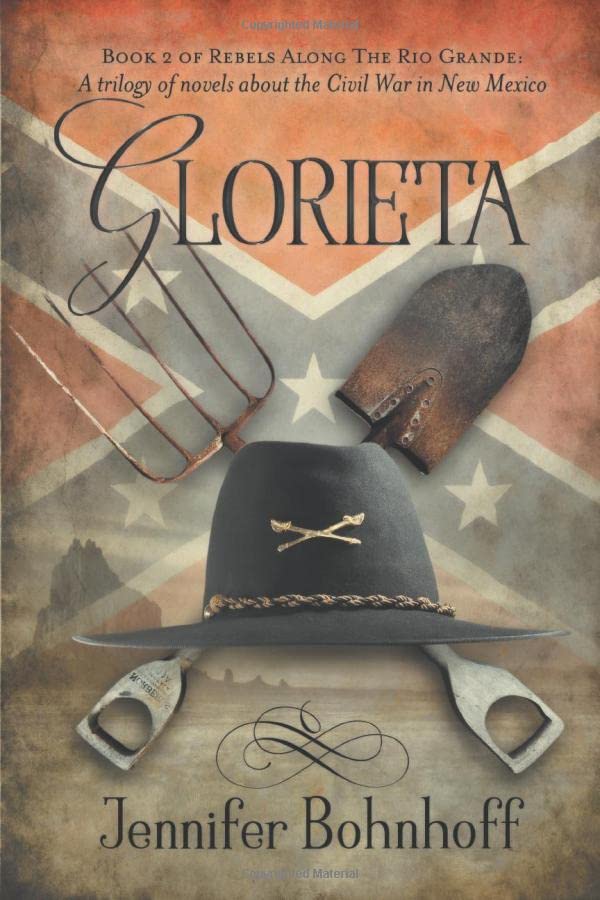

illustration by Ian Bristow in The Worst Enemy

illustration by Ian Bristow in The Worst Enemy The weather was no kinder in the mountains east of Santa Fe, where the Santa Fe Trail snaked through Glorieta Pass on its way to Fort Union, where the Confederate Army hoped to capture a wealth of Union supplies. The Texans won another tactical victory at the Battle of Glorieta, but returned to their supply train to find it burned. That night, Davidson wrote that “a severe snow storm arose and snow fell to the depth of a foot and several of our wounded froze to death.”

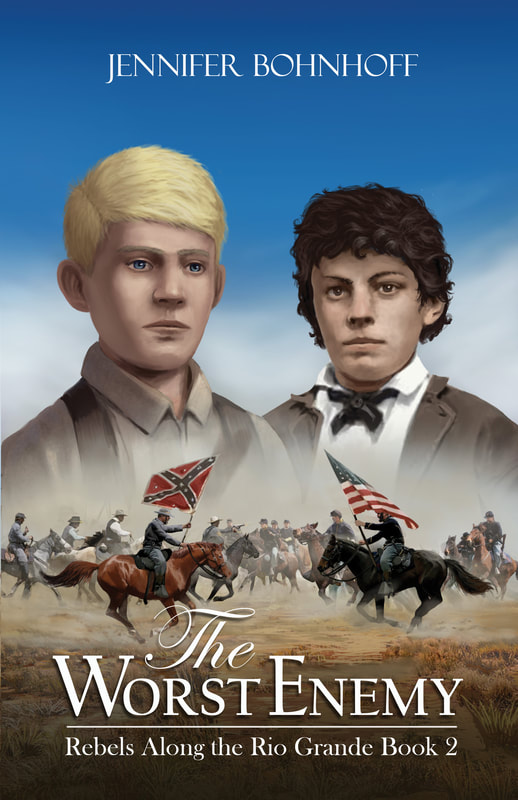

illustration by Ian Bristow in The Famished Country

illustration by Ian Bristow in The Famished Country  map by Matt Bohnhoff, included in The Famished Country

map by Matt Bohnhoff, included in The Famished Country In a letter to John McRae, the father of Alexander McRae, a native South Carolinian who fought for the Union, General Sibley blamed the countryside itself for his retreat.

“You will naturally speculate upon

the causes of my precipitate evacuation

of the Territory of New Mexico

after it had been virtually conquered.

My dear Sir, we beat the enemy

whenever we encountered him.

The famished country beat us.”