What we call Veterans Day began as Armistice Day, the day that World War I officially ended in 1918.

At the time that the United States entered World War I in 1917, one-third of the Native population was not recognized by the U.S. government as American citizens. Despite this fact, 12,000 Native Americans volunteered for military service. Some Native Soldiers joined to gain respect as warriors. Others joined because they believed it would prove their patriotism and help them receive citizenship, or to seek a better life for themselves and their families. Few knew that their Native languages would play an important role in the Great War.

The Cherokee Code Talkers continued their work until the end of the war. Soldiers from the Assiniboine, Comanche, Crow, Hopi, Lakota, Meskwaki (also known as Fox Indians), Mohawk, Choctaw, Seminole, Creek and Tlingit nations were also used. Col. Alfred Wainwright Bloor, commander of the 142nd Infantry, 36th Infantry Division, later stated that his regiment, possessed a company of Indians who spoke twenty-six different languages or dialects, only four or five of which were ever written. This made it almost impossible for Germans to translate.

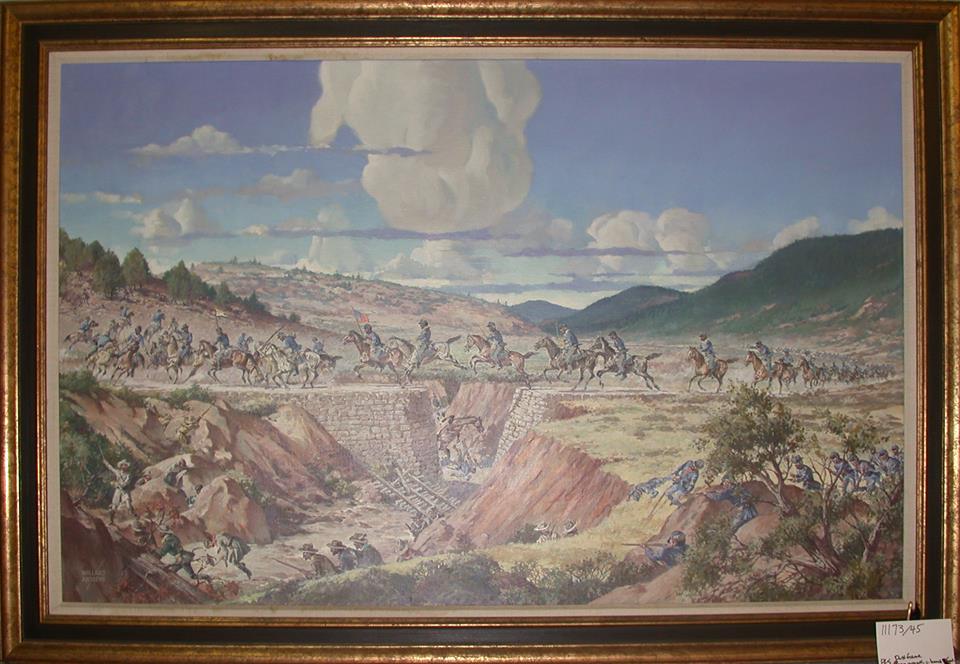

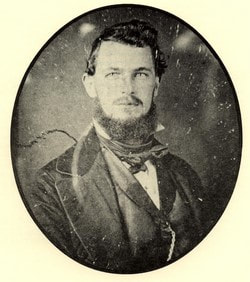

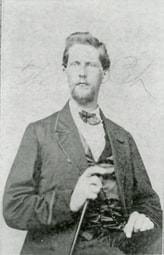

The most famous of the World War I Native Code Talkers was Pvt. Joseph Oklahombi a Choctaw Code Talker with Company D, 1st Battalion, 141st Regiment. During October 1918, Oklahombi and the 23 fellow soldiers in his company came across a German machine gun nest while they were cut off behind enemy lines. Oklahombi and his company rushed to the enemy’s position, captured it, and used the captured machine gun to pin down the enemy. Four days later, the 171 German soldiers surrendered. Oklahombi was awarded the World War I Victory Medal and a Silver Citation Star for his bravery, and France awarded him the Croix de Guerre.

As they had in World War I, other tribes continued to serve as Code Talkers in World War II.

This Veteran's Day, let's remember those soldiers who did not fight with guns, but with words, and all the others who fought to protect freedoms that they did not share in.