“Walnut pie?” my critic partners wondered. “What’s that? What goes into it? What does it taste like?”

Creator: Rainer Lesniewski | Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

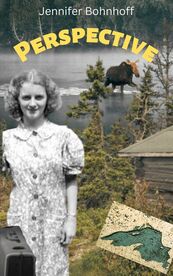

Creator: Rainer Lesniewski | Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto Isle Royale is a long, thin island in Lake Superior, the westernmost of the Great Lakes. To some people, Lake Superior looks like a wolf looking to the left, and Isle Royale is the eye.

The recipe I finally settled on is very simple, like I assume my characters, living in an isolated island forest, would be most likely to make. It uses maple syrup, which was then produced on the island in small quantities for use by the local inhabitants. I made a test pie and shared it with my family and they pronounced it a winner, so here it is.

Walnut Pie

(Don’t have your own pie crust recipe? Click here for one of mine.)

Preheat oven to 375°

Place 1 ½ cup chopped walnuts on a baking sheet.

Bake 5-7 minutes to toast the nuts and bring out the flavor.

Mix together:

½ cup brown sugar

2 TBS flour

1 ¼ cup maple syrup

3 TBS melted butter

¼ tsp salt

3 eggs

1 tsp vanilla extract

Stir in toasted walnuts. Pour into shell.

Bake for 40-45 minutes. Let cool completely before slicing and serving.