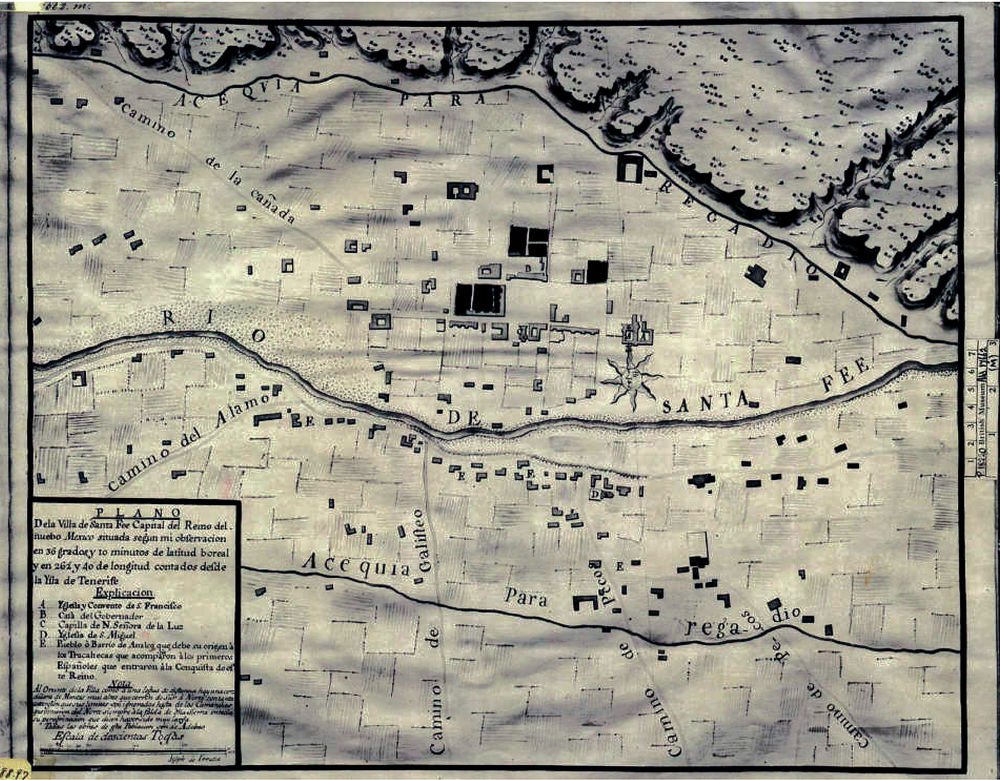

From The Civil War in Texas and New Mexico, by Steve Cotrell.

From The Civil War in Texas and New Mexico, by Steve Cotrell.  From Where Duty Calls. Illustration by Ian Bristow

From Where Duty Calls. Illustration by Ian Bristow  Jemmy. Ian Bristow, illustrator

Jemmy. Ian Bristow, illustrator  A Box of Hardtack. From Hardtack and Coffee by John D. Billings

A Box of Hardtack. From Hardtack and Coffee by John D. Billings  From Where Duty Calls. Illustrated by Ian Bristow

From Where Duty Calls. Illustrated by Ian Bristow When I can read my title clear

to mansions in the skies,

I bid farewell to every fear,

and wipe my weeping eyes.

Let cares, like a wild deluge come,

and storms of sorrow fall!

May I but safely reach my home,

my God, my heav’n, my All.