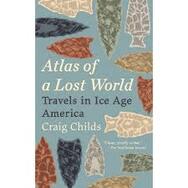

Can old stories remember events from thousands of years before their telling?

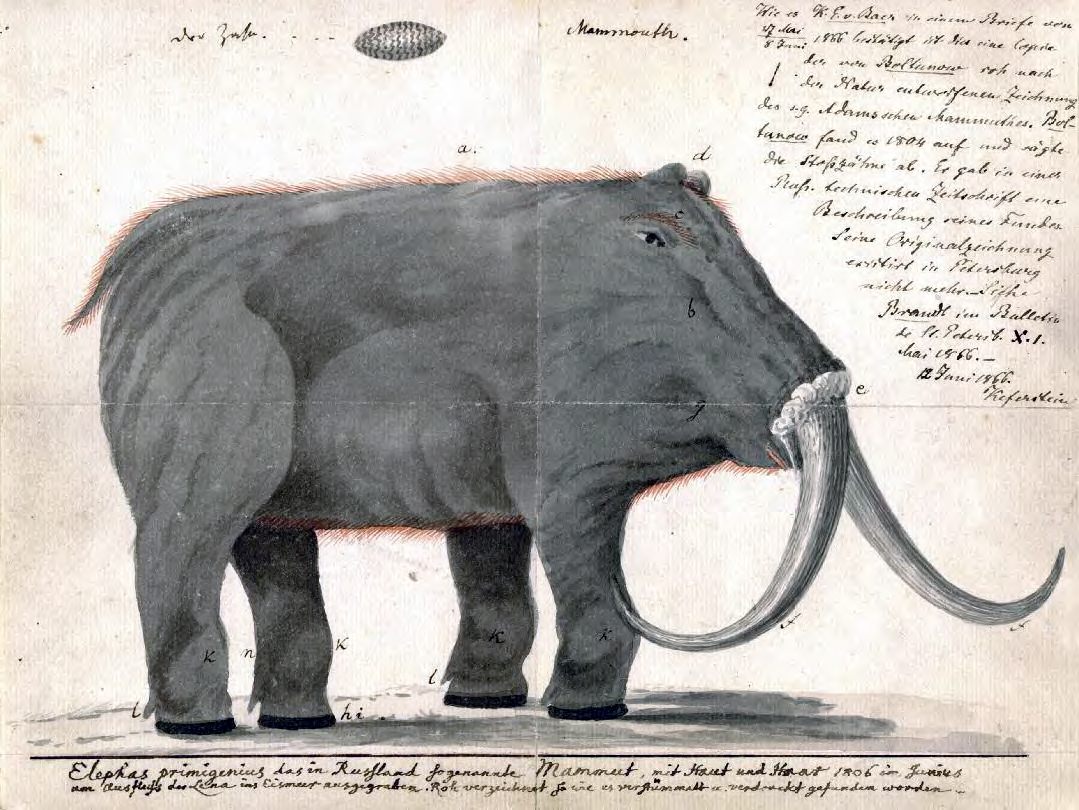

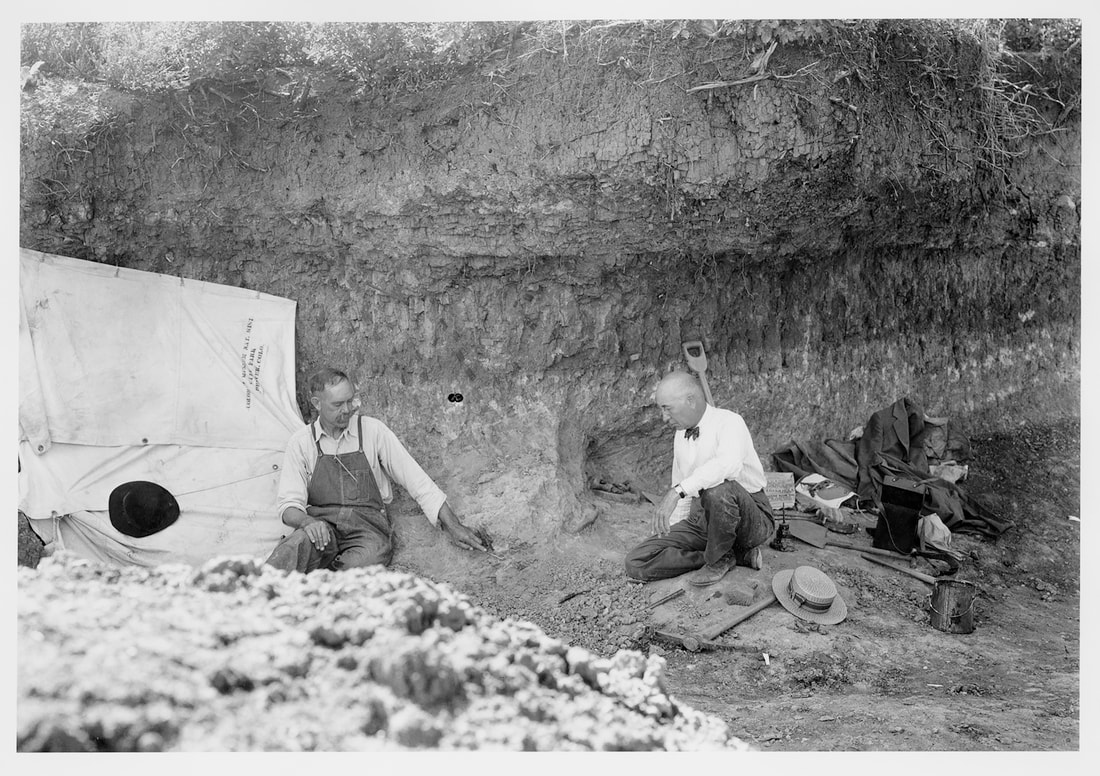

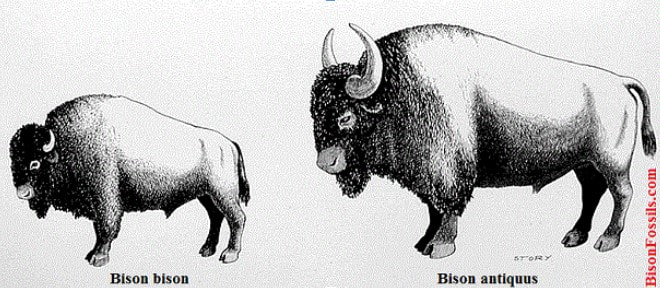

Backs like hills? Long teeth? Could these monsters be mammoths or mastodons?

Several generations? Since mammoths are thought to have gone extinct approximately 11,000 years ago, those are very long generations, indeed. But longer still is the memory of the people who were still telling stories about these creatures.

The booklinks in the above blog are for my recommended book lists on Bookshop.org, an online bookseller that gives 75% of its profits to independent bookstores, authors, and reviewers. If you click through my book lists and make a purchase on Bookshop.org, I will receive a commission, and Bookshop.org will give a matching commission to independent booksellers. But if you’re not looking to buy, browse my lists and find the books you’re interested in at your local library.