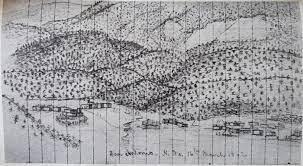

A sketch of San Antonio, New Mexico, by A. Petticolas, Confederate soldier

A sketch of San Antonio, New Mexico, by A. Petticolas, Confederate soldier This visiting neighbor told me he’d like to get his hands on a novel entitled Fiddlers and Fishermen because it was set in the east mountains. He’d searched, but he’d never been able to find a copy. That set me on a mission that began on Google, went to the public library, and finally to rare booksellers. What I discovered was that Fiddlers and Fishermen is one of two books written by Benjamin Frederick Clark. Born in Kansas in 1873, Clark moved into a cabin in Sandia Park, New Mexico in 1927. He passed away in that same cabin on May 30, 1947. He was 74 years old.

Clark’s other book is a small tome of poems. Entitled Melodious Poems from the Hills, it was published in 1945 under the pen name of Sandia Bill by Crown Publications. I managed to get a copy delivered to my local library through interlibrary loan. The copy is signed, in pencil, by the author. A second pencil notation, reading “gift of the author 6/30/45” is written along the gutter of the first page. There is a picture of Clark playing his fiddle in the frontpages. I have included it here.

Melodious Poems from the Hills has ninety-six pages. Some pages have two short poems on them. Most have one poem, and a few poems span a couple of pages. The first poem, “When I Am Dead,” is mentioned in his obituary and is the reason he was cremated.

When I Am Dead

Just wrap me in a shroud

And burn me, that the vapors may

Help form some lovely cloud.

Then place my pictures and my dolls,

And my ashes pure and clean,

‘Neath my rosevine and that tree

That always is so green.

Just leave the earth plain and smooth--

I want no omark or stone.

Just let the yard look like it did;

When in flesh, it was my home.

Take care of my sweet rosevine

And that evergreen tree –

This still my home will be;

And may flowers bloom around by tome

While gay robins sing for me.

This was one of my favorites, and seems appropriate in a year that saw so much of the west burning:

The Dying Monarch

Slowly expiring on the mountainside,

Who only a few hours ago,

Was the embodiment of health and pride.

His kindred pines for miles around,

And neighboring aspens, oaks, and firs

Are slowly tumbling to the ground

In bulks of smoldering embers.

The Lively squirrels and cheerful birds

From these parts have fled,

And they’ll be homeless for awhile,

For their friendly trees are dead.

Stands here the monarch of the forest,

Preaching a sermon as he expires,

Broadcasting his message to the world:

“Oh, men, be careful with your fires.”

Like the poem above, many of Sandia Bill’s poems are about the nature that surrounded him. Some are about the people, mostly ranchers, who he associated with. A few tell tales of love lost and found, of pretty women, dangerous men, and faithful old dogs, horses, and mules. This one, dear reader, I find speaks his heart, and mine.

I Am Thankful

And perhaps I’ll never be.

But I am in love with many things

And they’re all in love with me.

I am thankful for the sweet sunshine,

For snow, the clouds, and summer showers.

I am thankful for the Love Divine,

For butterflies, the birds, and flowers.

I am thankful for the girl I love

With eyes so soft and blue;

I am thankful for the stars above,

But more thankful, dear, for you.

I have yet to get my hands on a copy of Fiddlers and Fishermen. The only copy I’ve managed to locate is housed in the special collections in Zimmerman Library on the University of New Mexico campus, and they are not willing to circulate it through interlibrary loan. The only way I can read this 76 page novella is to make an appointment to read it at the library. Zimmerman’s old reading room is a beautiful, contemplative space. I did much of my undergraduate study there because it was such a peaceful place. Perhaps someday soon I will jump through the hoops to make this appointment happen.