Read considered studying medicine after graduation. As a way to pay for it, he joined the local unit of the Royal Army Medical Corps and received a commission in the Green Howards, a Yorkshire Regiment. By the time he entered the University of Leeds, he’d decided that medicine wasn’t for him, so he transferred from the Medical Corps to the Officer Training Corps, where he found himself surrounded by men who had come through Eton or other public schools. Compared to them, Read felt provincial.

When the War broke out, Read left his studies and was shipped overseas. He found that he was far more comfortable dealing with the sixty or so men in his platoon than the other officers. His platoon was filled with men who had done hard work in the mines and factories of Durham and North Yorkshire. Many were older and more experienced than he, who became a captain in his early twenties, but he developed a good repoire with them. His fellow officers struck him as “snobbish and intolerant.”

He soon realized that “all the proud pretensions which men had acquired from a conventional environment” became insignificant at the front, and his fatalistic soldiers with their “Every bullet has it billet. What’s the use of worryin’?” attitude coped better than “men of mere brute strength, the footballers and school captains.”

Politically, Herbert Read was what the English call a “Quietist Anarchist.” He was no waver of flags and felt no fervor for one people over another. He expressed hope that the relationships that he had developed in the trenches would lead to new social movement after the war, and that class conflict and nationalities would be abandoned for a more egalitarian, universal social order. He saw signs that the world had wearied of war and was ready to put aside nationalism in this remembrance:

Kneeshaw goes to War

Ernest Kneeshaw grew

In the forest of his dreams

Like a woodland flower whose anaemic petals

Need the sun.

Life was a far perspective

Of high black columns

Flanking, arching and encircling him.

He never, even vaguely, tried to pierce

The gloom about him,

But was content to contemplate

His finger-nails and wrinkled boots.

He might at least have perceived

A sexual atmosphere;

But even when his body burned and urged

Like the buds and roots around him,

Abash'd by the will-less promptings of his flesh,

He continued to contemplate his feet.

2

Kneeshaw went to war.

On bleak moors and among harsh fellows

They set about with much painstaking

To straighten his drooping back:

But still his mind reflected things

Like a cold steel mirror — emotionless;

Yet in reflecting he became accomplish'd

And, to some extent,

Divested of ancestral gloom.

Then Kneeshaw crossed the sea.

At Boulogne

He cast a backward glance across the harbours

And saw there a forest of assembled masts and rigging.

Like the sweep from a releas'd dam,

His thoughts flooded unfamiliar paths:

This forest was congregated

From various climates and strange seas:

Hadn't each ship some separate memory

Of sunlit scenes or arduous waters?

Didn't each bring in the high glamour

Of conquering force?

Wasn't the forest-gloom of their assembly

A body built of living cells,

Of personalities and experiences

— A witness of heroism

Co-existent with man?

And that dark forest of his youth --

Couldn't he liberate the black columns

Flanking, arching, encircling him with dread?

Couldn't he let them spread from his vision like a fleet

Taking the open sea,

Disintegrating into light and colour and the fragrance of winds?

And perhaps in some thought they would return

Laden with strange merchandise --

And with the passing thought

Pass unregretted into far horizons.

These were Kneeshaw's musings

Whilst he yet dwelt in the romantic fringes.

3

Then, with many other men,

He was transported in a cattle-truck

To the scene of war.

For a while chance was kind

Save for an inevitable

Searing of the mind.

But later Kneeshaw's war

Became intense.

The ghastly desolation

Sank into men's hearts and turned them black --

Cankered them with horror.

Kneeshaw felt himself

A cog in some great evil engine,

Unwilling, but revolv'd tempestuously

By unseen springs.

He plunged with listless mind

Into the black horror.

4

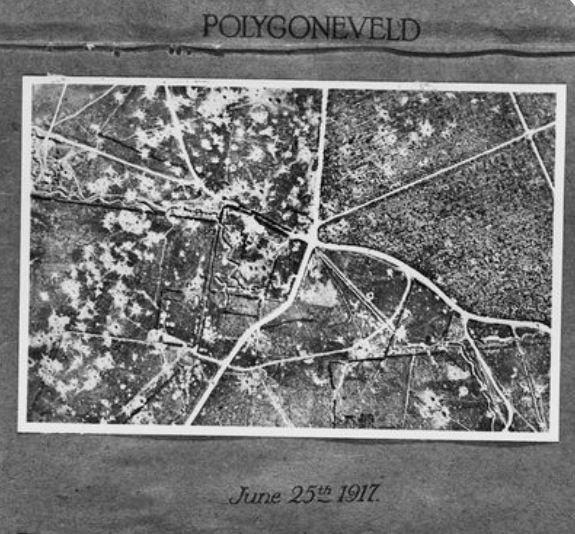

There are a few left who will find it hard to forget

Polygonveld.

The earth was scarr'd and broken

By torrents of plunging shells;

Then wash'd and sodden with autumnal rains.

And Polygonbeke

(Perhaps a rippling stream

In the days of Kneeshaw's gloom)

Spread itself like a fatal quicksand, --

A sucking, clutching death.

They had to be across the beke

And in their line before dawn.

A man who was marching by Kneeshaw's side

Hesitated in the middle of the mud,

And slowly sank, weighted down by equipment and arms.

He cried for help;

Rifles were stretched to him;

He clutched and they tugged,

But slowly he sank.

His terror grew --

Grew visibly when the viscous ooze

Reached his neck.

And there he seemed to stick,

Sinking no more.

They could not dig him out --

The oozing mud would flow back again.

The dawn was very near.

An officer shot him through the head:

Not a neat job — the revolver

Was too close.

5

Then the dawn came, silver on the wet brown earth.

Kneeshaw found himself in the second wave:

The unseen springs revolved the cog

Through all the mutations of that storm of death.

He started when he heard them cry " Dig in!"

He had to think and couldn't for a while.

Then he seized a pick from the nearest man

And clawed passionately upon the churned earth.

With satisfaction his pick

Cleft the skull of a buried man.

Kneeshaw tugged the clinging pick,

Saw its burden and shrieked.

For a second or two he was impotent

Vainly trying to recover his will, but his senses prevailing.

Then mercifully

A hot blast and riotous detonation

Hurled his mangled body

Into the beautiful peace of coma.

6

There came a day when Kneeshaw,

Minus a leg, on crutches,

Stalked the woods and hills of his native land.

And on the hills he would sing this war-song:

The forest gloom breaks:

The wild black masts

Seaward sweep on adventurous ways:

I grip my crutches and keep

A lonely view.

I stand on this hill and accept

The pleasure my flesh dictates

I count not kisses nor take

Too serious a view of tobacco.

Judas no doubt was right

In a mental sort of way:

For he betrayed another and so

With purpose was self-justified.

But I delivered my body to fear --

I was a bloodier fool than he.

I stand on this hill and accept

The flowers at my feet and the deep

Beauty of the still tarn:

Chance that gave me a crutch and a view

Gave me these.

The soul is not a dogmatic affair

Like manliness, colour, and light;

But these essentials there be:

To speak truth and so rule oneself

That other folk may rede.