Towards the end of The Bent Reed, my middle grade novel set in Gettysburg during the Civil War, the main character finds her father working in his carpentry shop. He is sawing planks to make coffins, using the wood from Rose's Wood Lot, a small field that stood near what became known as Devil's Den. The woodlot had been the scene of fierce fighting. Most of the trees had lost all their leaves. Many had never recovered. Pa laughs sadly and says that it is fitting for men to be buried in wood that had died the same day as they. As Pa works, others are exhuming bodies hastily buried in fields and roadsides throughout the area. A month after this scene, President Lincoln will come to dedicate a new cemetery. He gives the Gettysburg Address at that dedication.  Not every Union soldier got the benefit of being buried in a coffin. In I Married A Soldier, a memoir of Army life in the Southwest during the 1850s-1870s, Lydia Spencer Lane explains that wood was so scarce that it was customary to forgo burying coffins. She was told in Santa Fe that bodies were carried to the church in one, but removed and rolled in old blankets before being consigned to the tomb. Thus, coffins could be used and reused indefinitely. This was not acceptable to people who had been raised in the East, who did everything within their power to create coffins for their dead. Ms. Lane explains that, when there was not enough lumber at hand to make a coffin, old packing boxes and commissary boxes were brought into requisition. She recalled one officer who died at a post in Texas and was carried to his final resting place in a very rough coffin which had marked, in great black letters along the side, "200 lbs. bacon."  In Where Duty Calls, the first book in Rebels Along the Rio Grande, my trilogy set in New Mexico during the Civil War, a Confederate soldier who dies on pneumonia while on the campaign trail is buried in a coffin created from packing crates. William Kemp, the dead soldier, is an actual person, and the record of his death is part of the official records of Sibley's campaign to capture the west and its gold.  Jennifer Bohnhoff is the author of historical fiction novels for middle school readers through adults. Book two of Rebels Along the Rio Grande will be published by Artemesia Publishing in August, 2023 and is available for preorder on Bookshop.org.

5 Comments

The Pike's Peak Gold Rush, which began a decade after the California Gold Rush, attracted a hundred thousand miners and prospectors to the Pike's Peak Country of western Kansas Territory and southwestern Nebraska Territory. These men were known as the "fifty-niners." Gold was first discovered a decade earlier, in July, 1848 by a group of Cherokee on their way to California over the Cherokee Trail. The Cherokee did not stop to work the stream beds, but they reported their find to members of their tribe. William Green Russell, a Georgian who was married to a Cherokee woman, was working in the California Gold fields when he heard about the reported gold in the Pikes Peak region. He organized a party that included his two brothers and six companions, and in February 1858 they set out for Colorado. They finally hit pay dirt in July at the mouth of Little Dry Creek on the South Platte, in the present-day Denver suburb of Englewood. By the middle of the 1860s, most of the easy to get gold was gone. Placer deposits and shallow hard-rock mines were depleted. Men were giving up by the droves, selling their claims to richer men and companies who had the resources to acquire the materials required to go after ore that was deposited deeper in the ground or to chemically extract gold from mixed ore. Although there was still plenty of gold in them thar hills, the rush was over.  Jennifer Bohnhoff' is an educator and author who lives in the mountains east of Abuquerque, New Mexico. Her next novel, The Worst Enemy, begins in the gold fields of Colorado. It is now available as to preorder, and will be released on August 15th.  Historical fiction, when written well, has equal parts truth and fiction to it. It not only tells a good story, but helps readers understand a period in time. One of the most interesting and satisfying parts of writing historical fiction is researching the history and portraying it accurately. This can also be one of the most frustrating parts of writing historical fiction, especially when readers point out inaccuracies and anachronisms that in a work. It's happened to me many times. Sometimes the reader is wrong, like the editor who told me that there were no Germans in France during World War II. More often, though, they are right, and I have slipped something in that isn't accurate. Sometimes, however, the problem isn't with a misinformed reader or a gaffe on my part. Sometimes the problem goes farther back than either the writer or the reader. Such is the case with the cause of death for William F. Marshall. There are parts of William F. Marshall's story that we do know. We do know, for instance, that he was elected by the men in Company F of the Colorado Volunteers to the position of 2nd Lieutenant. Several of my readers have questioned this, but it is true that companies elected their officers during this period. We know that he was not universally liked by his men. Some diaries left by men call him imperious or haughty. Finally, we know that he was the last man to die during the Battle of Apache Canyon, the first day and portion of the Battle for Glorieta Pass.  Historical records provide us the names of both the first and the last man shot in the Battle of Apache Canyon. The first was the company's captain, Samuel Cook, who received a buck and ball wound to the thigh. He continued to fight and was injured several times before being carried off the field. He recovered from his wounds. William Marshall was not so lucky. We know that he was the last man shot on that fateful day. We know that he was carried to Pigeon's Ranch, where a hospital had been established. We know that he died early in the morning of the next day. But the details of his death are sketchy. The reason the details are sketchy are that the sources we have for this battle are largely military reports or the memoirs of those who were there. Military reports may be very good at telling us who was on the right flank and who led a particular assault. They tell us who died, but they don't include the particulars of that death. Memoirs often tell the particulars, or at least what the veteran who wrote them remembers. One source that I read said that Marshall was supervising the destruction of confederate arms abandoned on the battlefield when he picked up a rifle by its muzzle and hit it against a stump in order to bend the barrel. The gun discharged into his stomach and he died just before dawn of the next day. However, another account tells it differently. According to this man, Marshall took a handgun from a Texas prisoner when it discharged in his face. Face or stomach? Handgun or rifle? While a writer may never be sure, he or she had to choose one story or the other to include in his or her work of historical fiction.  William Marshall's death is part of the story that Jennifer Bohnhoff includes in The Worst Enemy, book two of the series Rebels Along The Rio Grande, which tells the story of the Confederate invasion of New Mexico. It is scheduled to be released on August 15, 2023 and is available for preorder now. A New Mexico native and former New Mexico History teacher, Mrs. Bohnhoff hopes she chose the right set of circumstances for the 2nd Lieutenant's death.  Mules were the backbone of both Confederate and Union Armies during the American Civil War. They pulled the supply wagons, the limbers and caisons for cannons, and the ambulances. One of the reasons that the Confederate Invasion of New Mexico failed was that they couldn't keep enough mules to hauls supplies. Many of the Confederate Army's mules were lost to theft by Indians and locals, and death due to starvation and disease. The night before the battle of Valverde, a Union spy named Paddy Graydon managed to spook the Confederate's mules, who stampeded down to the Rio Grande. There Union soldiers managed to round them up. In Hardtack and Coffee: The Unwritten Story of Army Life, Civil War veteran John D. Billings shares the story of another mule stampede. During the night of Oct. 28, 1863, Union General John White Geary and Confederate General James Longstreet were fighting at Wauhatchie, Tennessee. The din or battle unnerved about two hundred mules, who stampeded into a body of Rebels commanded by Wade Hampton. The rebels thought they were being attacked by cavalry and fell back. To commemorate this incident, one Union soldier penned a poem based on Tennyson's Charge of the Light Brigade. Charge of the mule brigade Half a mile, half a mile, Half a mile onward, Right through the Georgia troops Broke the two hundred. “Forward the Mule Brigade!” “Charge for the Rebs!” they neighed. Straight for the Georgia troops Broke the two hundred. “Forward the Mule Brigade!” Was there a mule dismayed? Not when the long ears felt All their ropes sundered. Theirs not to make reply, Theirs not to reason why, Theirs but to make Rebs fly. On! to the Georgia troops Broke the two hundred. Mules to the right of them, Mules to the left of them, Mules behind them Pawed, neighed, and thundered. Breaking their own confines, Breaking through Longstreet's lines Into the Georgia troops, Stormed the two hundred. Wild all their eyes did glare, Whisked all their tails in air Scattering the chivalry there, While all the world wondered. Not a mule back bestraddled, Yet how they all skedaddled-- Fled every Georgian, Unsabred, unsaddled, Scattered and sundered! How they were routed there By the two hundred! Mules to the right of them, Mules to the left of them, Mules behind them Pawed, neighed, and thundered; Followed by hoof and head Full many a hero fled, Fain in the last ditch dead, Back from an ass's jaw All that was left of them,-- Left by the two hundred. When can their glory fade? Oh, the wild charge they made! All the world wondered. Honor the charge they made! Honor the Mule Brigade, Long-eared two hundred!  Jennifer Bohnhoff is a Native New Mexican who writes in the high, thin air of the Sandia Mountains. Mules play an important role in Where Duty Calls, her historical novel set in New Mexico during the Civil War. Glorieta. The second book in the series, The Worst Enemy the sequel to Where Duty Calls, will be published by Kinkajou Press, a division of Artemesia Publishing, in August, 2023. This article was originally posted April 27, 2017. Clafouti is a French dessert that looks beautiful and is simple to make. It might be just the thing to make in early June, when cherries are ripe and we think back to D-Day and the sacrifices our Allied troops made when they stormed the beaches of Normandy to wrest control from German troops.  Clafouti 1 1/2 sweet cherries, pitted 1 cup milk 1/2 cup whipping cream 1/2 cup flour 4 eggs 1/2 cup sugar 1/8 tsp salt 1 tsp almond extract or kirsch confectioner's sugar for dusting Preheat oven to 350° Butter a 1 ½ quart baking dish with low sides. Arrange the cherries in a single layer in the dish. Combine the milk and cream in a saucepan and heat but do not boil. Remove from heat and use a whisk to add the flour a little at a time until well blended. Wisk together the eggs, sugar and salt in a small bowl. Add the kirsch or almond extract and the heated milk mixture and pour over the cherries. Bake 45-55 minutes, until browned and puffed, yet still soft I the center. A knife stuck into the center should come out clean. Transfer to a rack and cool slightly before dusting with confectioner’s sugar. Serve warm. 4 servings. Jennifer Bohnhoff is an author who writes historical fiction for middle grade through adult readers. Elephants on the Moon is her story about a French girl who joins the Resistance fighters in preparing for the D-Day invasions, and is available in paperback and ebook.

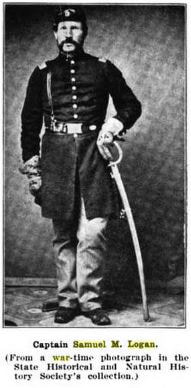

Both the image and the recipe featured here are adapted from Chuck Williams: Simple French Cooking, (San Francisco, Weldon Owens, Inc., 1996)  Samuel M. Logan isn’t a name that many would recognize as a Civil War personality, but he played an important supporting role in the Colorado Volunteers and has a small role in my novel The Worst Enemy, the second of three books in Rebels Along the Rio Grande. Little is known about his childhood. Military records suggest he was born on December 18, 1821 in Ohio, who the names of his parents and whether he had any siblings is unknown. Samuel M. Logan was a Mexican American War veteran who was working as a blacksmith in Denver when the Civil War broke out. He didn’t waste any time in showing on which side his sympathies lay with a grand gesture. On April 24, 1861, just days after the bombardment of Fort Sumter, the southern sympathizers who owned Wallingford and Murphey’s Mercantile on Larimer Street in downtown Denver raised the Confederate stars and bars on the pole atop their building. The flag attracted an angry mob of pro-Union sympathizers who threw rocks at the store and demanded that the flag come down.  The Worst Enemy Illustration by Ian Bristow The Worst Enemy Illustration by Ian Bristow Logan swang into action -- literally. He climbed a hitching rail and swung himself onto the roof of the store. Accounts of what happened next contradict each other. Some accounts say that the Marshal showed up at this point, dispersed the crowd, and allowed Wallingford and Murphey to continue flying the Confederate colors. Other accounts say that Logan pulled down the flag and ripped it to shreds as the crowd cheered him on. Whichever is the case, Logan’s stunt made him popular enough that he was able to recruit a company of men to follow him into the volunteer army that William Gilpin, the newly appointed governor of the territory, was raising. In those days, whoever brought in the required number of men was given the commission to lead them. Samuel M. Logan, blacksmith and climber of roofs became Captain Samuel M. Logan of Company B of the Colorado Volunteers. Logan’s reputation for quick and dramatic action led him to receive some orders that made for exciting press releases. In late August, his Company was ordered to clean out the Criterion, a saloon that was a notorious gathering place for secessionists. Logan and his men stormed in with bayonets fixed. They confiscated a large pile of weapons and ammunition and became the darling heroes of Denver. However, the same qualities that made him a man of action didn’t make him a beloved leader. By September, Company B had delivered a petition to Governor Gilpin requesting that he remove Captain Logan, “whose overbearance and tyranny have become untolerable.” The Governor chose to ignore this petition.  Logan’s Company engaged the enemy on both days of the Battle of Glorieta. On the second day, it was part of the group that Major John Chivington led over the top of Glorieta Mesa in what was intended to be a flanking movement to attack the Confederate force in the rear. Instead, they overshot and instead of fighting in the Battle of Pigeon’s Ranch, descended from the mesa at Johnson’s Ranch, where they were able to destroy the Confederate baggage train, effectively destroying the Confederate Army’s ability to wage war in New Mexico. From then on, Logan’s rise through the military was tied to that of John Chivington’s. Both were men of fiery and decisive action who held a “take no quarter” attitude, especially when it came to treatment of American Natives. By spring of 1864, Logan had been promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, bypassing other officers who argued for more leniency in dealings with the Plains Tribes. With Chivington, Logan participated in the infamous Sand Creek Massacre in November 1864. Both men managed to avoid prosecution for their part in the massacre because both mustered out before charges could be filed, but their implication in Sand Creek would permanently destroy their hopes for a future in politics.  The 1870 census indicates that Logan was married, had fathered three children, two of whom died in childhood. He was working as a freighter. Logan died in 1888, at age 61. He was buried in Riverside Cemetery in Denver. His wife, Mary, and son Samuel are buried with him.  Jennifer Bohnhoff is a writer and educator who lives in New Mexico. The Worst Enemy, her second book in Rebels Along the Rio Grande, a trilogy of novels about the Civil War in New Mexico, will come out this August. |

ABout Jennifer BohnhoffI am a former middle school teacher who loves travel and history, so it should come as no surprise that many of my books are middle grade historical novels set in beautiful or interesting places. But not all of them. I hope there's one title here that will speak to you personally and deeply. Categories

All

Archives

March 2025

|