New Mexico has been peopled for tens of thousands of years. The radiocarbon dating of footprints found at White Sands has pushed back human occupation to somewhere between 23,000 and 21,000 years ago. As far as we know, for much of that time, the different people occupied different areas without any formal boundaries.Spheres of influence overlapped. People shared the same hunting grounds and wintering areas, sometimes peacefully and sometimes not.  That all changed with the coming of the Spanish in the sixteenth century. The first peoples with a written system to document their intentions, they declared the land the property of the Spanish King and divided it into grants. From early on, the Spanish recognized three different types of land grants. Private grants were awarded to soldiers, nobility, and important people. Community grants were given to groups of people, particularly genizaro. The settled Indian populations, which means the Puebloans, received grants that protected their pueblos and fields from Spanish incursion to some degree. Those tribes that did not live a settled lifestyle did not receive land grants. Following the Mexican-American War, the United States took control of the territory. The treaty ending the war recognized the Pueblo land grants. In 1863, President Lincoln presented 19 Pueblo Governors with canes to show that the Federal government recognized their authority. Today there are still 19 Pueblo tribes in New Mexico. Each pueblo is a sovereign nation. Not all Indigenous peoples in New Mexico lived settled lives. The nomadic tribes: the Apache, Navajo and Comanche tended to live within a range of land, but they did not stay in one place. The Navajo had fields and orchards, but they did not tend them year round. These groups were not given land grants by either the Spanish or the Mexican governments when they controlled New Mexico. In 1837, Sam Houston, the President of the Republic of Texas, proposed that the Comanches be given their own land. Their summer range encompassed much of western Texas, large portions of what is now Oklahoma and New Mexico, and the edges of Colorado and Kansas. The Comanches were fierce fighters. Giving them their own territory would, the Texans hoped, stop them from killing settlers and attacking wagon trains. The Texas congress did not ratify Houston's proposal, and the Comanche's were eventually given a reservation in Oklahoma. Apache tribes have little reservations scattered over several western states, and the Navajo reservation straddles the states of Utah, Arizona and New Mexico. In the 1970s, Navajo tribal chairman Peter McDonald suggested that the Navajo homeland become the fifty-first state, giving its occupants more autonomy and control. The biggest issue at the time was the refusal of Utah to allow the Ft. Hall Navajos to build a casino on their land. While his proposal received national attention in 1974, New Mexico, Arizona and Utah all refused to support it. If the population within the reservation grows, this proposal might be renewed.  Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired New Mexico History teacher who now writes historical fiction. She has written about the state during the Civil War in Where Duty Calls, during World War I in A Blaze of Poppies, and is currently at work on a novel set 12,000 years ago during the Folsom period.

3 Comments

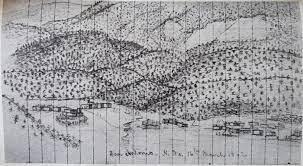

A sketch of San Antonio, New Mexico, by A. Petticolas, Confederate soldier A sketch of San Antonio, New Mexico, by A. Petticolas, Confederate soldier A while back, a neighbor was over and we were talking about the history here on the east side of the Sandia Mountains. He was raised here. I spent my teens in Albuquerque, the city that lies just west of the Sandias. I hiked in the mountains plenty, and I had friends that lived over here, especially after I got to high school. Manzano High School was, and still is the high school that kids from the east mountains attended. I’ve always been interested in the geology of the mountains. Its most ancient of records are the rocks, which tell us that what is now the top of a mountain used to be at the bottom of a sea. But I didn’t become interested in the human history of the east mountains, its small towns, and the people who inhabited them until I moved here in 2017. This visiting neighbor told me he’d like to get his hands on a novel entitled Fiddlers and Fishermen because it was set in the east mountains. He’d searched, but he’d never been able to find a copy. That set me on a mission that began on Google, went to the public library, and finally to rare booksellers. What I discovered was that Fiddlers and Fishermen is one of two books written by Benjamin Frederick Clark. Born in Kansas in 1873, Clark moved into a cabin in Sandia Park, New Mexico in 1927. He passed away in that same cabin on May 30, 1947. He was 74 years old.  Back in 1947, Sandia Park was the area uphill from the little village of San Antonito. A dirt road went through the middle of it on its way up to the crest of the mountain. My area was on the outskirts of a village called La Madera, whose economy was based on truck farming, limestone mining, and timber. The stream that was the lifeblood of La Madera has ceased to flow and the town has become a ghost town. I drive a little over six miles to get my mail at the Sandia Park Post office. Clark’s other book is a small tome of poems. Entitled Melodious Poems from the Hills, it was published in 1945 under the pen name of Sandia Bill by Crown Publications. I managed to get a copy delivered to my local library through interlibrary loan. The copy is signed, in pencil, by the author. A second pencil notation, reading “gift of the author 6/30/45” is written along the gutter of the first page. There is a picture of Clark playing his fiddle in the frontpages. I have included it here. Melodious Poems from the Hills has ninety-six pages. Some pages have two short poems on them. Most have one poem, and a few poems span a couple of pages. The first poem, “When I Am Dead,” is mentioned in his obituary and is the reason he was cremated. When I Am Dead When I am dead, don’t cry for me; Just wrap me in a shroud And burn me, that the vapors may Help form some lovely cloud. Then place my pictures and my dolls, And my ashes pure and clean, ‘Neath my rosevine and that tree That always is so green. Just leave the earth plain and smooth-- I want no omark or stone. Just let the yard look like it did; When in flesh, it was my home. Take care of my sweet rosevine And that evergreen tree – This still my home will be; And may flowers bloom around by tome While gay robins sing for me. This was one of my favorites, and seems appropriate in a year that saw so much of the west burning: The Dying Monarch Here stands the monarch of the forest, Slowly expiring on the mountainside, Who only a few hours ago, Was the embodiment of health and pride. His kindred pines for miles around, And neighboring aspens, oaks, and firs Are slowly tumbling to the ground In bulks of smoldering embers. The Lively squirrels and cheerful birds From these parts have fled, And they’ll be homeless for awhile, For their friendly trees are dead. Stands here the monarch of the forest, Preaching a sermon as he expires, Broadcasting his message to the world: “Oh, men, be careful with your fires.” Like the poem above, many of Sandia Bill’s poems are about the nature that surrounded him. Some are about the people, mostly ranchers, who he associated with. A few tell tales of love lost and found, of pretty women, dangerous men, and faithful old dogs, horses, and mules. This one, dear reader, I find speaks his heart, and mine. I Am Thankful I am not a rich or famous man, And perhaps I’ll never be. But I am in love with many things And they’re all in love with me. I am thankful for the sweet sunshine, For snow, the clouds, and summer showers. I am thankful for the Love Divine, For butterflies, the birds, and flowers. I am thankful for the girl I love With eyes so soft and blue; I am thankful for the stars above, But more thankful, dear, for you. I have yet to get my hands on a copy of Fiddlers and Fishermen. The only copy I’ve managed to locate is housed in the special collections in Zimmerman Library on the University of New Mexico campus, and they are not willing to circulate it through interlibrary loan. The only way I can read this 76 page novella is to make an appointment to read it at the library. Zimmerman’s old reading room is a beautiful, contemplative space. I did much of my undergraduate study there because it was such a peaceful place. Perhaps someday soon I will jump through the hoops to make this appointment happen. Jennifer Bohnhoff’s newest novel, Where Duty Calls, is set in New Mexico during the Civil War and is the first in a trilogy. Written for middle grade readers, it is a quick, informative read for adults. She lives and writes in the mountains east of Albuquerque, New Mexico, close to the camp the Confederate Army used as they advanced towards Santa Fe in the spring of 1862 that is pictured above. .

|

Don't see what you're looking for?

I am in the process of moving all my blog entries to a different blog site. Eventually, this page will go away. If you're looking for something and it's not here, try my new site, or email me and suggest I write a blog on the topic you are interested in.

ABout Jennifer BohnhoffI am a former middle school teacher who loves travel and history, so it should come as no surprise that many of my books are middle grade historical novels set in beautiful or interesting places. But not all of them. I hope there's one title here that will speak to you personally and deeply. Categories

All

Archives

March 2025

|