One of the first and most successful compact cameras was the Vest Pocket Kodak camera, or

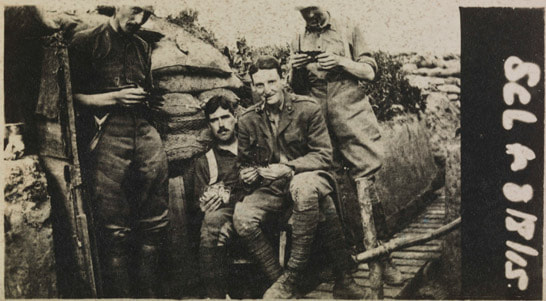

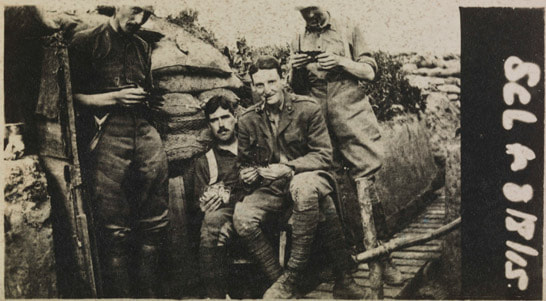

The beginning of the twentieth century was a time of massive change in society and in technology. One of the new inventions during this period was a camera so compact, it could slip into a man’s pocket. One of the first and most successful compact cameras was the Vest Pocket Kodak camera, or  ‘VPK.’ Priced between $6 and $15 depending on the features, about 5,500 VPKs were sold in Britain in 1912, the first year it was produced. The next year over 28,000 of these cameras were sold in Britain. By the time the model was discontinued in 1926, over 2 million had been sold, making it one of the most popular and successful cameras of its day.  The Vest Pocket Kodak measured just 1’ by 2½’ by 4¾’. The lens panel expanded away from the film roll by way of a pair of lazy-tongs struts that were either outside or inside a leather bellows, depending on the model. Prior to this period, cameras were made from wood to make them lightweight. The VPK was made from metal.  In 1915, Kodak introduced the ‘Autographic’ Vest Pocket Kodak. Based on a patent taken out in 1913 by American inventor Henry Gaisman, this camera used a roll of film that had a thin tissue of carbon paper inserted between the film and the backing paper. Photographers could open a small flap in the back of the camera to uncover the backing paper. The photographer then used a metal stylus to write information on their negatives which would appear on their finished prints. The VPK took film negatives that were 1⅝” by 2½” -- larger than a postage stamp. Pictures could be enlarged for easier viewing. So many soldiers bought cameras to record their travels and experiences that the VPK became known as ‘The Soldier’s Kodak.’ Thousands of American ‘doughboys’ recorded their wartime experiences using this handy little camera.  Heinrich Dieter, one of the characters in Jennifer Bohnhoff's award winning historical novel A Blaze of Poppies, owns and uses a vest pocket Kodak both at home in Southern New Mexico and while serving as a medic on the battlefields of France.

0 Comments

November is National Novel Writing Month, and I’m participating again this year. I’ll be working on a middle grade historical novel inspired by, but not in any way based on my summer hike, the Tour du Mont Blanc. As I researched the scenes of my story, I discovered that Charles Dickens toured Switzerland in the summer of 1846. One of the places that both Dickens and I went to was the hospice at the top of the Great Saint Bernard Pass. This Hospice is the highest winter habitation in the Alps. It is also the place where the eponymous dog breed got its start. Run by Augustinian monks, it has been sheltering and protecting travelers since its founding, nearly a thousand years ago, by Bernard of Menthon. Etchings from Dicken’s time demonstrate that little has changed in the past two hundred years. One thing that has changed is access to one of the hospice’s more morbid rooms: the mortuary. In Dickens’ time, the mortuary that still stands beside the Hospice was a great curiosity to travelers. Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in Switzerland, published in 1843 included it among the must-see sites. It is known that Dickens took a copy of this travel guide with him. He describes the room in a letter he wrote to John Forster on September 6, 1846: Beside the convent, in a little outhouse with a grated iron door which you may unbolt for yourself, are the bodies of people found in the snow who have never been claimed and are withering away – not laid down, or stretched out, but standing up, in corners and against walls; some erect and horribly human, with distinct expression on the faces; some sunk down on their knees; some dropping over one on side; some tumbled down altogether, and presenting a heap of skulls and fibrous dust. The door to the mortuary is closed now. I do not know whether I could have pleaded to gain access, and I suspect that the bodies that had remained there are now long gone. One set of bodies in particular fascinated both Dickens, who included her in his novel Little Dorrit, and Murray, who includes a description in his travel guide. She is a mother who Dickens describes as “storm-belated many winters ago, still standing in the corner with er baby at her breast.” Dickens pities the mother and gives her voice: “Surrounded by so many and such companions upon whom I never looked, and shall never look, I and my child will dwell together inseparable, on the Great Saint Bernard, outlasting generations who will come to see us, and will never know our name, or one word of our story but the end.” Dickens did not care to create a backstory for the poor, frozen woman and her child. Neither shall I. But his words continue to keep her alive in the hearts of readers some two hundred years after her death. Jennifer Bohnhoff writes novels for middle grade and adult readers. Many of them are historical in nature.

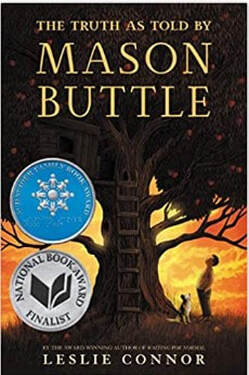

Americans call November 11th Veteran's Day, and use the day to honor veterans of all wars . But originally November 11th observed Armistice Day, the when World War I ended, at least officially. . There are many cemeteries in Belgium and France that hold the remains of Americans killed during the First World War. Unlike the cemeteries in Normandy, which contain those killed during the D-Day Invasion in World War Two, many of the World War 1 cemeteries recieve very few visitors each year.  The Aisne-Marne American Cemetery covers 42.5-acres at the foot of the hills that holds Belleau Wood. It contains the graves of 2,289 war dead. Most of these men came from the U.S. 2nd Division, which included the 4th Marine Brigade, and fought in the 20 day long battle for Belleau Wood. Also buried here are soldiers from the 3rd Division who arrived in Château-Thierry and blocked German forces on the north bank of the Marne throughout June.and July of 1918. The second largest number of New Mexicans killed in France during World War I died at the Battle of Chateau-Thierry. Many of them were part of Battery A of the New Mexico National Guard, which came from Roswell. The 28 New Mexicans killed in this battle are interred at the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery together with 2,261 AEF soldiers. The carved marble at the top of the pillars that flank the entrance to the French Romanesque chapel depict soldiers engaged in battle in the trenches. One of the stained glass windows inside displays the insignias of American divisions engaged in the area. Another window has the crests of countries on the Allied side of the war. The inside of the chapel is inscribed with the names of 1060 men who were missing after the battles. Some of those names have a small brass star next to them. That means the body was later found and identified. It has been over a hundred years since World War I ended. There are no veterans left for us to honor. But we must never forget, and we must continue to honor the men who went "over there" and fought to keep us free.  Jennifer Bohnhoff is a native New Mexico with an interest in history. In 2019, she had the privilege of touring the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery and walking through Belleau Wood. That experience led her to writing A Blaze of Poppies, a novel about New Mexico's involvement in World War I. November is National Novel Writing Month, and I’m participating again this year. I’ll be working on a middle grade historical novel inspired by, but not in any way based on my recent hike around the Mont Blanc massif. I don’t have a title for this work as of yet; perhaps you, dear readers can help me determine a good title sometime during November. What I do know thus far is that my novel will be set in 1799-1800 and will take place in Great Saint Bernard Pass, a route through the Alps that travels up the Rhone Valley from Martigny, Switzerland to Aosta, Italy. Great Saint Bernard pass is not the prettiest of passes, but it is convenient and offers the additional attraction of the Saint Bernard Hospice, the highest winter habitation in the Alps, at the top of the pass. The Hospice is also the place where the eponymous dog breed got its start.  When I went through the Great Saint Bernard Pass this past September, I traveled by bus: not a city bus or a school bus, but the kind of tour bus that holds perhaps fifty passengers, with two big upholstered seats on each side of a central aisle. The road itself, which is now called highway E27, was paved, but it had only two lanes, one in each direction, and it had more hairpin turns than a roller coaster. More than once, I was convinced that the bus wasn’t going to be able to negotiate a turn. A few times I was right, and the bus driver had to throw the bus into reverse and make an extra cut in order to make it around a tight bend. I’ve been doing a lot of research this past month, and I’ve discovered that Charles Dickens went through the Great Saint Bernard Pass (and yes, there is a Lesser Saint Bernard Pass.) in September of 1846 when he was touring Switzerland. Dickens did not ride in a tour bus. In his day, the path was so rocky that the only way to travel along what was then called the Chemin des Chanoines, or the pathway taken by the canons of the hospice, was on foot or astride a donkey or horse. Even carriages could not make the journey; they were disassembled at Bourg-Saint-Pierre, the highest village on the Swiss side, then carried over the pass by porters and reassembled on the Italian side.  Dickens includes his perception of traveling Great Saint Bernard Pass in his novel Little Dorrit. In Book 2, chapter 1, his travelers ride through “the searching old of the frosty rarefied night air at a great height,” through a landscape marked by “barrenness and desolation. A craggy track, up which the mules, in single file, scrambled and turned from block to block, as through they were ascending the broken staircase of a gigantic ruin.” In these upper reaches of the pass, “no trees were to be seen, nor any vegetable growth, save a poor brown scrubby moss, freezing in the chinks of rock.” At the front of the mules is “a guide on foot, in his broad-brimmed had and round jacket, carrying a mountain staff or two upon his shoulder.”  I’ve seen a painting of another rider on a mule, guided by another man who knew the trail, but that is a story best saved for another blog. Jennifer Bohnhoff writes for middle grade and adult readers. Most of her books are works of historical fiction. You can read more about her and her book on her website. Merriam Webster defines a trope as a recurring element or a frequently used plot device in a work of literature or art. One common trope in not only literature but in cartoons is the mismatched duo, particularly a big guy partnered with a little guy. Often the smaller character is also physically weaker and needs the protection of his big friend. In return, he supplies the ideas that move the story forward. The big guy, often a misunderstood gentle giant or suffering a mental deficiency or disability, needs his little buddy to keep him out of trouble. The big guy/little guy partnership has been used repeatedly in cartoons. When my sons were little, the TV cartoon that used this trope most obviously was Pinky and the Brain. The cartoon focused on two genetically enhanced laboratory mice who resided in a cage inside the Acme Labs research facility. Brain, the littler of the two mice, was highly intelligent, self-centered and scheming. Pinky was Brain’s sweet-natured but feeble-minded henchman. In every episode, Brain devised a new plan to take over the world, but his plans always failed, with hilarious results.  Not all works that use the big guy/ little guy trope are funny, however. Probably the most famous and most literary of the trope’s treatments has been in Of Mice and Men, John Steinbeck’s 1937 novella. In it, George Milton is the little, smart guy who tries to protect Lennie Small, a slow thinking giant of a man who does not understand his own strength. The two displaced ranch workers move from job to job in Depression-era California, until fate catches up to them and Lennie can no longer protect his friend. The story is a tragedy and appears on the American Library Association's list of the Most Challenged Books of the 21st Century because many consider the material both offensive and racist, but it is also a beautiful depiction of the difficulties some people seem to never be able to shrug off, and the importance of watching after each other. It is a book that is, by turns, noble and base, vulgar and tender, and is frequently taught in high school courses. I consider it a little too mature for middle school readers, but hope that middle schoolers will have the chance to encounter it when they are older.  A book that features the big guy/ little guy trope, but is appropriate for middle school readers is Rodman Philbrick’s Freak the Mighty (Scholastic Paperbacks; Reprint edition, June 1, 2001, ISBN-13: 978-0439286060) In this novel, the big guy is Max, a teenage giant with a learning disability and a terrible secret. The little guy is Kevin, whose tiny body is wracked with a syndrome that is slowly killing him. Together, they are Freak the Mighty, and they can overcome bullies and brutes. This story does not end up happily, either, but the reader is left with a sense of hope for the future. The book was made into a movie titled The Mighty, and stars Kieran Culkin and an all-star cast. When I taught middle school Language Arts, this was one of my favorite books to share. The movie to book comparison always led to good discussions on how characters were presented and what and why certain plots lines, scenes and themes were left out of the movie version.  The most hopeful middle grade big guy/ little guy book I found was Leslie Connor’s multiple-award winning The Truth As Told by Mason Buttle (Katherine Tegen Books; Reprint edition, January 7, 2020, ISBN-10: 0062491458.) Mason is a big, sweaty kid whose learning disabilities make reading and writing impossible. His down and out family has suffered several deaths and the sell-off of their orchard land that had been their livelihood for generations. Then, the body of Mason’s best friend, Benny Kilmartin, was found in what remained of the family orchard and he is shunned by the town and bullied by neighboring boys. Mason’s luck begins to change when little guy Calvin Chumsky befriends him. Together, the two manage to enjoy their circumstances while the investigation drags on, and Mason tries to convince Lieutenant Baird that he is not responsible for Benny’s death. The truth does come out, in ways that no one has anticipated. I think it is important for parents and teachers to talk with children about the big guy/little guy trope. The line between trope and stereotype is slim, indeed. Not every big guy is a gentle giant with limited mental ability. Some big guys are big on brains, too. Others are not gentle at all. Nor is every little guy a genius trapped in a weak frame. But regardless of its limitations, the trope remains an important one in literature and worthy of study. I think comparing books to cartoon depictions and movies is a good place to start. Perhaps middle schoolers would be better prepared for Steinbeck if they began with Philbrick and Connor.  Jennifer Bohnhoff is a retired High School and Middle School Language Arts and History teacher. She is the author of historical novels for both middle grade and adult readers. The book links in this article are to Bookshop.org, an online bookseller that gives 75% of its profits to independent bookstores, authors, and reviewers. As an affiliate, Jennifer Bohnhoff receives a commission when people buy books by clicking through links on her blog or browsing her shop at bookshop.org/shop/jenniferbohnhoff. A matching commission goes to independent booksellers. However, Ms. Bohnhoff is just as happy when people borrow books from their local library or shop at their local independent booksellers. I am always deeply saddened when I hear people tell me that New Mexico History is boring. I used to teach the subject at the middle school level, and I confess that the textbook was, indeed boring. Fitting thousands of years of history into a book involves leaving out all the details that makes the story exciting I strived to tell those stories in my classroom, and the result was that a lot of kids found that history wasn’t just a list of names, dates, treaties and battles. History was the story of people who were trying, just like my students, to do the best they could under whatever circumstances they were given. These four novels to a good job of giving the history of New Mexico a human face.  Dennis Herrick’s Winter of the Metal People: The Untold Story of America's First Indian War (Sunbury Press, 2013, ISBN-10 1620062372) tells the story of Spanish conquistador Francisco Coronado's 1540-1542.expedition into New Mexico and his occupation of a pueblo near what is now Bernalillo, on the banks of the Rio Grande. The site, which may be at what is now called Coronado Monument, Told from both a Spanish perspective derived from the chronicles the explorers left behind and from the (largely conjectured) perspective of the Puebloans, this well researched novel depicts the Tiguex War, the first battle between Europeans and Indians on what was to become American soil.  Loretta Miles Tollefson’s There Will Be Consequences: A Biographical Novel of Old New Mexico (Palo Flechado Press, 2022, ISBN 1952026059) tells the story of a very tumultuous time in New Mexico history. New Mexico, the distant and neglected area on the wild edge of the Spanish New World, had long been left to its own devices. The Spanish, busy with European wars and other colonies, had provided little, and expected little in return. New Mexicans had expected the same kind of negligence from the Mexican government when it revolted against Spain and established its own government. However, by 1837, Mexico had decided to exert more control over New Mexico, appointing governors from beyond its territory and demanding taxes that had long been waived. The northern half of the territory responded with a rebellion that left the Governor and key members of his administration dead, and a local man with indigenous ancestry and a set of local alcaldes set up in their place. In this well researched novelization of the events, Tollefson tells the story of this rebellion through the eyes of twelve of its participants and witnesses. Anyone who’s read anything of the period will recognize names such as Albino Pérez, José Angel Gonzales, Gertrudes "Doña Tules" Barceló, Father Antonio José Martinez, and Manuel Armijo. But Tollefson isn’t just reciting names and events. Her narrative makes the people in it come alive.  Mary Armstrong’s The Mesilla: Two Valleys Saga: Book One (Enchanted Writing Company, 2021, ASIN B093CPZ71B) tells its story through the eyes of fourteen years old, Jesus ‘Chuy’ Perez Contreras Verazzi Messi, who is apprenticed to his by his uncle, the noted Las Cruces attorney and politician, Colonel Albert Jennings Fountain. Bronco Sue, Oliver Lee, and Frenchy Rochas are among the historical figures that appear in this novel that takes place in the territorial period, when the area was struggling with range wars and trying to appear legitimate and worthy of statehood. It is filled with courtroom drama and the kind of background stories that spice up history and make the characters come alive. The first in a trilogy, this novel sets up the events that may have led to the unsolved murder of Fountain ten years later.  Finally, I am pleased to share that my own novel A Blaze of Poppies (Thin Air Publishing, 2021, ASIN B09HG16WBX) recently won the 2022 New Mexico Book Award in the category of New Mexico Historical Fiction. This novel tells the story of a young, female rancher in Southern New Mexico who is determined to keep the Sunrise Ranch in the family. Threatened first by Pancho Villa’s raid on nearby Columbus, New Mexico and by her own mother’s refusal to support her, Agnes Day becomes a nurse and serves behind the trenches in World War I France that are occupied by members of the New Mexico National Guard. New Mexico has a vibrant history made all the more interesting because of the mix of people who have inhabited a difficult to conquer landscape. Try one of these books and see for yourself. The book links in this article are to Bookshop.org, an online bookseller that gives 75% of its profits to independent bookstores, authors, and reviewers. As an affiliate, Jennifer Bohnhoff receives a commission when people buy books by clicking through links on her blog or browsing her shop at bookshop.org/shop/jenniferbohnhoff. A matching commission goes to independent booksellers. However, Ms. Bohnhoff is pleased if you borrow books from your local library or shop at your own local independent bookseller.

|

Don't see what you're looking for?

I am in the process of moving all my blog entries to a different blog site. Eventually, this page will go away. If you're looking for something and it's not here, try my new site, or email me and suggest I write a blog on the topic you are interested in.

ABout Jennifer BohnhoffI am a former middle school teacher who loves travel and history, so it should come as no surprise that many of my books are middle grade historical novels set in beautiful or interesting places. But not all of them. I hope there's one title here that will speak to you personally and deeply. Categories

All

Archives

March 2025

|