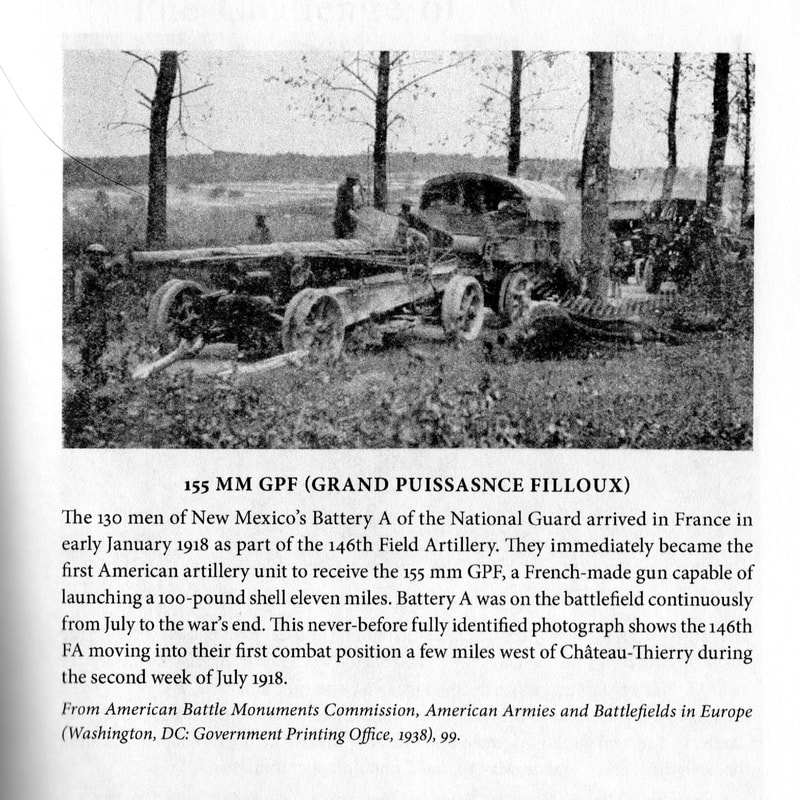

Black and white photograph of American soldiers and a small girl. The soldiers and the girl all hold rifles over their right shoulder. Photo: object 2023.122.1 in the Museum collection. https://collections.theworldwar.org/argus/final/Portal/Default.aspx?component=AAAS&record=16235ede-63d9-4183-b069-bc8362c450f1

Black and white photograph of American soldiers and a small girl. The soldiers and the girl all hold rifles over their right shoulder. Photo: object 2023.122.1 in the Museum collection. https://collections.theworldwar.org/argus/final/Portal/Default.aspx?component=AAAS&record=16235ede-63d9-4183-b069-bc8362c450f1

Picture: Joseph D. Marcelli wearing the play uniform made by his father, a tailor in New Jersey. Object ID: 2011.50.1 in the museum collection.

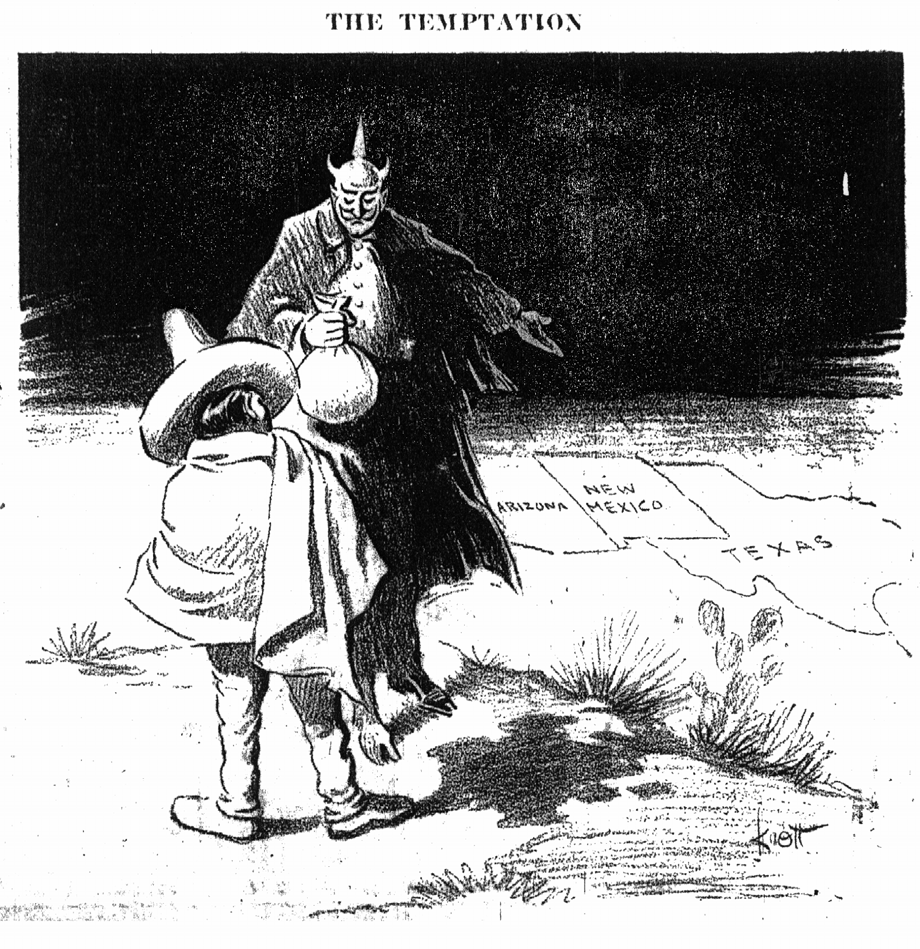

Another way that children learned to hate the enemy, and therefore war against him, was by ridiculing the other side. Nursery Rhymes for Fighting Times took common Mother Goose rhymes such as Humpty Dumpty, and adapted them to make the Germans, especially Kaiser Wilhelm, look ridiculous.

Jennifer Bohnhoff in an author who lives and writes in the mountains of central New Mexico. She wrote about World War I in her historical novel, A Blaze of Poppies.