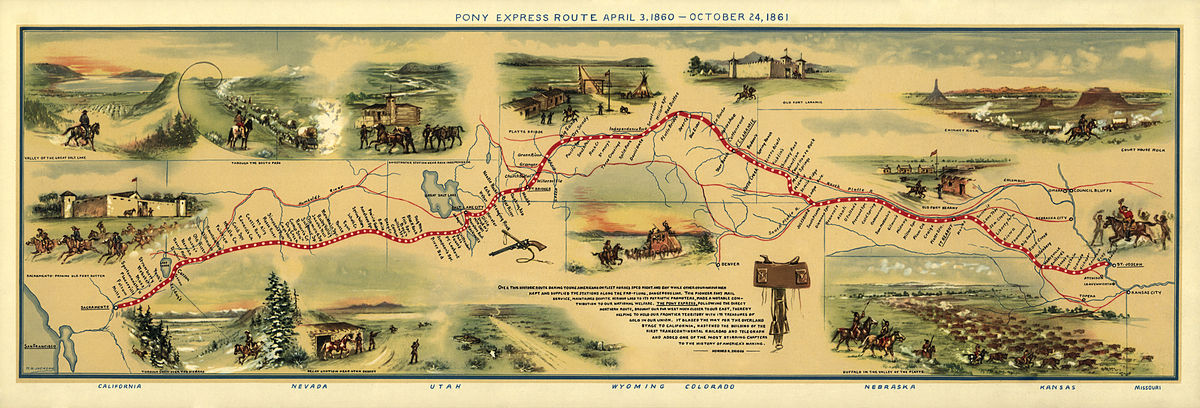

The approximately 1,900-mile-long route for the Pony Express began at St. Joseph, Missouri, the far west terminus of the telegraph line. It roughly followed the Oregon and California Trails to Wyoming’s Fort Bridger, then followed the Mormon Trail to Salt Lake City, Utah. After that, it went to Carson City, Nevada Territory on the Central Nevada Route, then passed over the Sierra Nevadas before it reached Sacramento, California. From there, the mail went downriver by boat to San Francisco. About 186 stations were set up about 10 miles apart along the route. Riders changed to a fresh horse each station. They rode night and day, stopping after 75–100 miles. In emergencies, and when the next rider was unavailable, riders might ride two stages back-to-back, spending over 20 hours on horseback. Some of the stations had bunkhouses in which the riders could sleep.

One of the most famous Pony Express deliveries was done by Robert Haslam, who later went by the nickname “Pony Bob.” Haslam was born in London, England in 1840. In April 1861, he rode 13 mustangs on an eight hour ride that took him through 120 miles of Nevada Territory. His route went through hostile Paiute Indian country. According to his journal, he engaged in a “running fight” with warring braves that lasted for “three or four miles.” During that fight, a flint-tipped arrow pierced his arm and another broke his jaw and knocked out five teeth. Haslam was able to escape after shooting the horses out from under several of the Paiutes.

In recognition of his rapid and dangerous ride, the Express Company awarded Haslam $100. Although not delivering the packet might have changed the outcome of the war, Haslam was unfazed. He said, “ It’s nothing to get all fussed about. I’m a Pony Express rider. It’s all part of the job.”

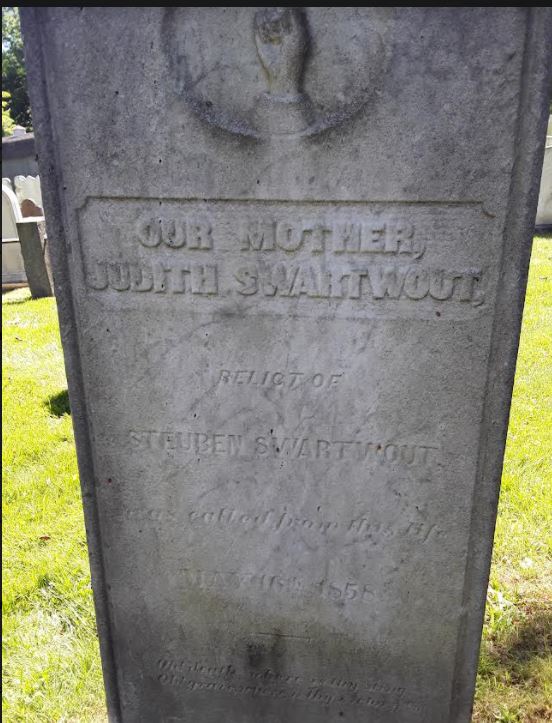

When the Pony Express stopped, Pony Bob became and express rider for Wells, Fargo & Company. As the Pacific Railway and telegraph lines pushed westward, he took other routes in increasingly remote areas. When there were no more express routes, he moved to Chicago, where he died, destitute, in 1912. His tombstone was paid for by long-time friend and fellow pony express rider, William “Buffalo Bill” Cody.