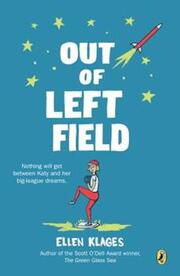

In Out of Left Field, youngest daughter, Katy Gordon is a baseball fanatic in a world where everything, except Little League admission rules, is changing. The San Francisco Seals, the hometown favorites for 50 years, are going away, to be replaced by the Giants. Sputnik is launched and schools in the south are being integrated. But Kay, who throws a mean pitch so singular that it doesn't even have a name, cannot join Little League because she's a girl. When her teacher assigns an American hero research paper, Katy delves deeply into the history of female baseball players in order to prove that the Little League rules make no sense.

This book has interesting, fully developed characters, and a plot line that shows how kids can change the world through activism, but it also paints a brilliant picture of what life was like in 1957. You can read this novel on its own, but it's even richer when read with its companion stories, Green Glass Sea and White Sands, Red Menace.

The book will help children explore what it is like to have parents divorce, being teased for being short, and the need to just be a kid. It is not a fast paced or exciting book, and the plot has no real surprises, but kids who have aspirations for the big league will find an affinity with Marcus and will appreciate knowing that even Golden Glove winners were kids once.

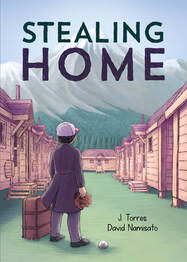

The story in Stealing Home is about Sandy Saito, a Canadian of Japanese descent whose life changes when Japan attacks Pearl Harbor. Sandy is a typical boy. He reads comic books and loves baseball, especially the local Japanese team, the Asahi. Suddenly, he is perceived as different and dangerous. The Canadian government begins treating ethnic Japanese as enemy aliens, taking away their radios and cars. He is excluded from games and taunted by other children. Finally, his family is separated and forced to move to internment camps with substandard facilities.

J. Torres and David Nashimoto tell a fictional story with so much emotion and historic accuracy that it reads like a memoir. I especially appreciated the extensive background information and resources for further study that are in the back of the book .

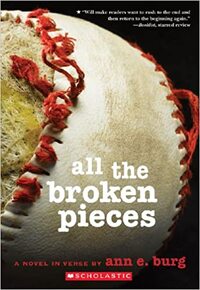

It's a story about baseball, but it’s even more about fitting in, adoption, discrimination, post traumatic stress disorder, guilt and sorrow, and the difficulty of soldiers returning to the US after the war. Both haunting and lyrical, this book goes beyond the usual baseball-themed books to show an emotional picture of a specific and difficult time in history. Matt Pin is a boy between cultures, who can show the reader both sides of the story with grace and courage.

I've got one copy of this novel. Tell me in the comments that you'd like it and I'll pick one lucky responder to get it!

However, I encourage readers to check with their local libraries first!

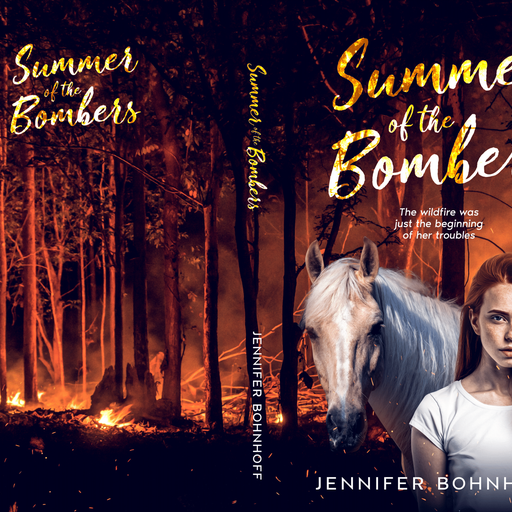

Jennifer Bohnhoff is an author of books for readers from middle grade to adult. She is not an avid baseball fan, but she is married to one and loves to sit in the stands, eat a hot dog, and take in the action. You can read more about her and her books on her website.