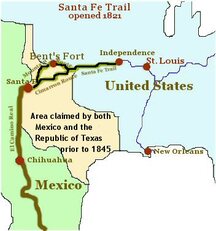

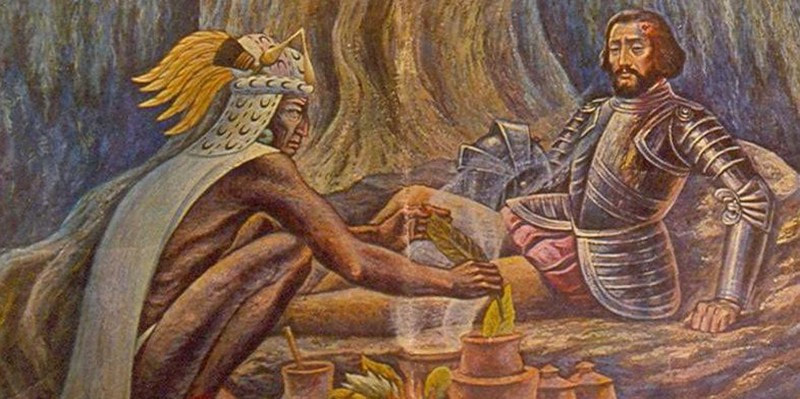

In 1598, Don Juan de Oñate led Spanish colonists to the upper valleys of the Rio Grande near Española, founding Santa Fe de Nuevo México. Accompanying him were Franciscan monks, charged with ministering to the Hispanos of New Mexico and spreading Christianity among the Native Americans. Central to their mission was providing daily mass, which included Holy Communion. According to the Catholic faith, the wine served during communion became, through transubstantiation, the blood of Christ shed for the redemptions of sinners.

The monks had a problem, however: wine was difficult to come by in New Mexico. One quarter of Spain’s foreign trade revenue came from wine exports, and Spain was keen to protect this income source. A 1595 Spanish law forbade the export of Spanish grapevines and made it illegal to plant them in foreign soil. Instead of having a local source for their sacramental wines, monks in the colonies had to rely on wine that had crossed the Atlantic Ocean and been brought up the Camino Real, a journey that took several months at best and often over a year.

The wine shipped from Spain was light pink in color and tasted like sherry, with an alcohol content of 18%, and 10% sugar content. The heavy stoneware jugs it traveled in held between 2.6 and 3.6 gallons and resembled the jugs used in Roman times. The jugs had a green glaze that leached lead applied to their interiors. Prolonged exposure to heat during the journey and the acidity of the wine exacerbated the leaching.

Soon, churches all over the region were planting and cultivating their own vineyards. By 1633, New Mexican viticulture was firmly established. But the relationship between Spanish settlers and Native Southwestern tribes deteriorated. In 1680, the Pueblo Revolt led to the expulsion of the Spanish settlers. During their twelve-year absence, many of their vineyards were destroyed.

In 1868, Jean Baptiste Lamy, the first bishop of Santa Fe invited Jesuit priests to settle in Albuquerque and establish the Immaculate Conception Parish. Originally from Naples, Italy, the priests brought with them their own winemaking techniques, which they used when they founded their own winery. Other Italians followed, becoming merchants in Albuquerque’s booming downtown. New Mexico’s wine production increased nearly tenfold in the next ten years. By 1880, New Mexico had twice as much acreage in grapevines as New York and ranked fifth in the nation for wine production. By 1900, New Mexico was producing almost a million gallons of wine a year.

Ovidio and Ettore Franchini, proprietors of Franchini Brothers store, enjoying a glass of homemade Italian wine ca 1910. (Photo courtesy of Henrietta Berger, Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico, 2009-03-04

Ovidio and Ettore Franchini, proprietors of Franchini Brothers store, enjoying a glass of homemade Italian wine ca 1910. (Photo courtesy of Henrietta Berger, Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico, 2009-03-04 Once again, New Mexico’s wine industry bounced back. Beginning in the 1970s, small commercial wineries began operating in New Mexico. There were four in 1979. Two years later, Hervé Lescombes a winemaker from Burgundy, France came to try his luck in the desert. Many other European investors followed. Today, more than 40 wineries and vineyards produce more than tens of thousands of gallons of wine annually in New Mexico, contributing millions of dollars to the state’s revenue.

Let us raise a glass to the tenacity of those who kept New Mexico’s wineries going, despite laws, rebellions, drought and flood.