The most plausible in my mind is that the Plains Indians, who fought the Buffalo Soldiers, thought that their dark skin and black curly hair looked much like the coloring and fur of the buffalo.

A second theory is that they were named after the thick buffalo-hide coats the troops wore during the winter.

A third theory is that they were awarded the name because of the ferocity and bravery of their actions.

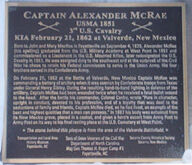

George Jordan, of K Troop, 9th Cavalry Regiment, earned his prestigious medal for repulsing a force of more than 100 Indians while he and his detachment of 25 men were stationed at Fort Tularosa, N. M., and then for holding his ground in an exposed position so that a larger force of Indians could not surround his command in Carrizo Canyon.