Patton at VMI

Patton at VMI

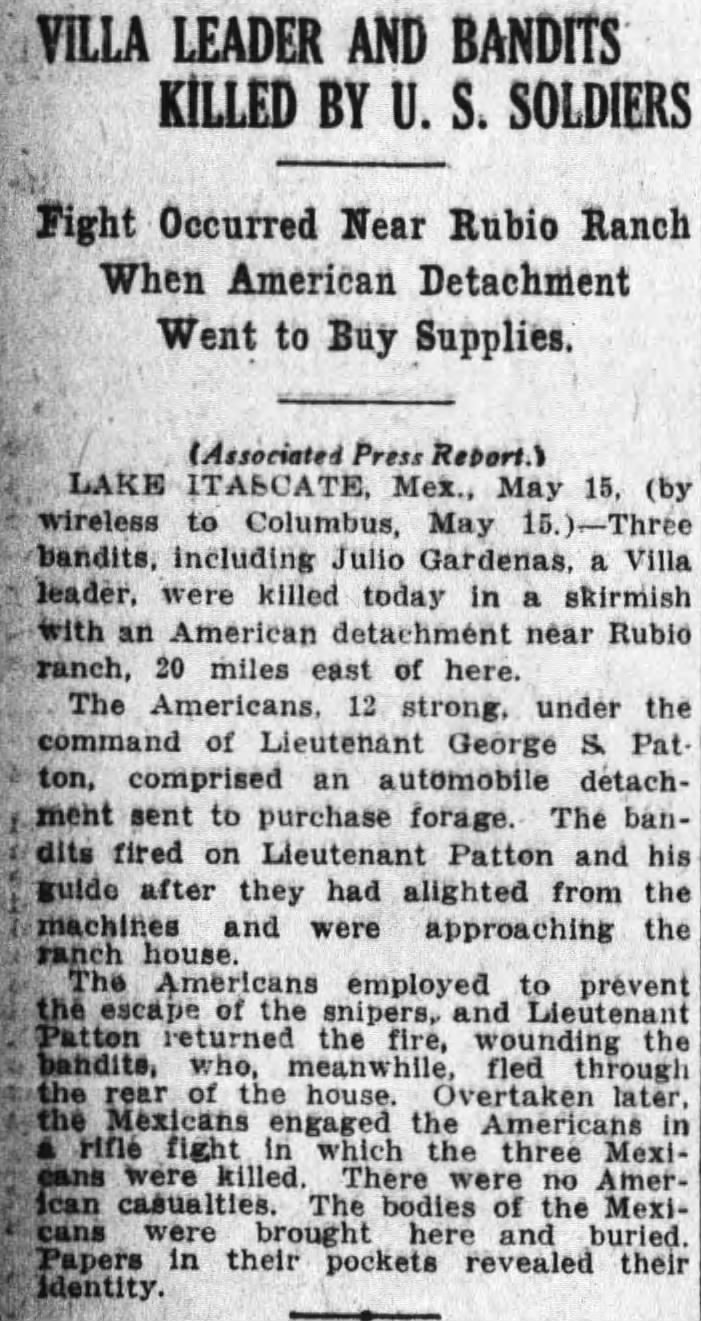

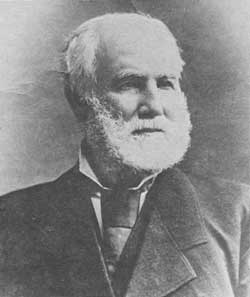

George Smith Patton Jr. was born into a life of privilege on November 11, 1885. His father was the district attorney for Los Angeles County and his mother was the daughter of Los Angeles’ first elected mayor. He went to VMI for one year before transferring to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where he proved himself to be a mediocre student but a brilliant athlete. It’s ironic, and I’m sure not coincidental that Patton’s statue at West Point is placed with his back towards the library.