based on the characters in

Where Duty Calls, book 1 of the

Rebels Along the Rio Grande Trilogy

Raul waited until heard the servant slip the timber into the braces, blocking the door. One couldn’t be too careful these days. The Confederates who’d been too sick or injured to head north after the Battle of Valverde had been in Socorro nearly two months, long enough to heal and wander the town looking for a little whiskey, a fight to pick, or a girl. Willing or unwilling didn’t matter. Anything to relieve their boredom. Mama was still young enough, and beautiful enough, to attract attention.

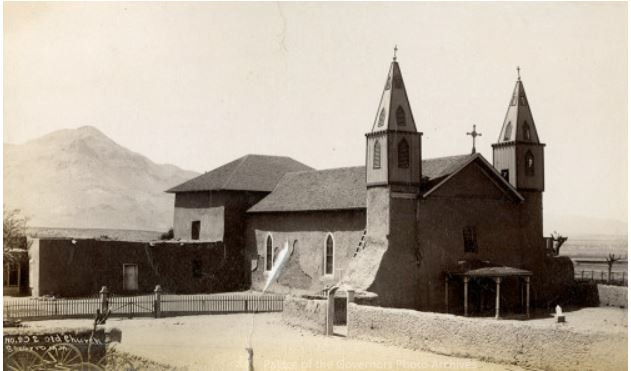

He looked up and down the dusty street. Finding it empty, he hitched the basket into the crook of his arm and headed toward San Miguel church, where he turned into the graveyard. Raul set the basket atop a sandy mound that had already begun to cement itself together again, healing like the girl beneath it never would. An image of Lupe stretched on her bed flashed into Raul’s mind. He moved the basket, horrified he might have placed it on her chest. He straightened and scanned the road. He hadn’t been followed.

“Mama told me to give this to you. She misses you. So do I.” Raul stuck his hand into the basket and pulled out a tortilla. He folded it in quarters and set it on the grave. Raul sat back on his heels and stared at the bit of bread. Lupe was beyond eating anything, ever again. Still, there was comfort in sharing with her. She had died at such a difficult time that none of the usual observances had happened; quickly buried, with no velorios, no neighbors bringing food, nothing to attract the attention of the Confederates. It had been a hard and lonely time for Mama, made harder by her husband and brother’s absence. There was not much that the two men agreed on, but they had appeared to be of one accord in hiding of the flock and stock from the Confederates. Raul tilted his head back, scanning high in the hills. Was either Papa or Tio watching him? Which one he should he be watching himself? They were so different from one another; he could not follow both.

A little whirlwind rose up, scoured from the earth by the afternoon heat. At the first sting of sand on his face, Raul closed his eyes and waited for it to pass. When he opened them again, the tortilla was covered with a fine dusting of grit. Raul stood up and dusted his trousers. The mice, or racoons, or whatever it was that ate the ofrendas left for the dead wouldn’t mind a little dirt with their meal.

He crossed to the low adobe wall at the back of the graveyard and looked around once more to be sure that no one watched before he sat atop it and swung his legs over. From the back of the church, he climbed into the hills, checking over his shoulder several times to see if he was being followed. The town seemed asleep, dazed by the heat of the day. Raul pulled the neckerchief from around his neck and mopped his face as another whirlwind rose into a swirling column of dirt, struck a gravestone, and collapsed on itself, dying almost before it had begun. It was only April, but already afternoons had become oppressive enough to create dust devils, diablos de polvo.

Raul dropped over a ridge and the village disappeared from sight. He scrambled up a sandy arroyo as it wound up into the hills. Gasping for breath, he switched the basket to his other arm.

“Mi’jo, you sound like an entire troop of soldiers,” a voice said from somewhere above him. Raul twisted his head back and saw his father, Cresenio, silhouetted against the sky.

“It’s this loose rock. It crunches and rolls under your feet.” Raul gestured down, and his father snorted.

“That, and you’re gasping like the bellows in the blacksmith’s shop. You don’t get out enough. You’re getting soft, like your uncle. Pretty soon, you’ll be good for nothing but balancing account books and arguing in court.”

Cresenio leaped down from the boulder and led the way up the arroyo. Raul slipped and slid as he struggled to keep up. His short legs could not match his father’s long strides, but he didn’t dare ask his father to slow down. Crescenio snapped his head to one side so that his words carried over his shoulder. “It’s a good thing it’s me who heard you coming, not some Apache. You would have looked like a porcupine by now.”

“You seen any Apaches?” Raul shaded his eyes and scanned the hills, which shimmered in the heat, making it almost impossible to pick out movement. He stumbled, nearly dropping the basket.

“I seen nothing.” Crescenio spit contemptuously, his voice tinged with bitterness. “No Indians. No soldiers, Union or Confederate. We’re wasting our time up here. But your uncle, he is too afraid of the Confederates.”

“Not much to be afraid of, at least for us men,” Raul said as he panted for breath. “Most are just limping, hollow-eyed skeletons. The rest are buried outside of town. Father Sanchez wouldn’t let them be buried in the churchyard.”

“They’re not the ones Tio’s afraid of.” Crescenio jerked his chin north, indicating the thin, green line delineating the bosque that flanked the Rio Grande. Somewhere down there, a defeated Confederate Army was limping its way back towards Texas. Raul had heard the rumors. Everyone in town had, and all eyes scanned the northern horizon for a return of the dust cloud that hung over an army on the move.

“Ah! You’ve captured a spy,” Tio Pedro said playfully. He set down the book that had been cradled in his lap and held out his hand. “I say we confiscate his basket and see what’s in it. How is that sister of mine?”

“She is lonely and bored, and still very sad,” Raul answered.

“But safe? And well? And Arsenio?” Crescenio demanded.

“Mama is safe. And well. And Arsenio is recovering.” Raul saw the slight tic of relief that his father didn’t want him to see. Crescenio wanted everyone to think he was steely and strong, but underneath the sharp exterior lay a man who loved his bubbly, vivacious wife, grieved for the daughter he had lost, and worried still for the son who had nearly accompanied his sister in death.

“We should be with her.” Crescenio gave his brother-in-law a sharp, sidewise glance.

“Not until those Texicans have passed through.” Tio responded, in an equally sharp tone. Clearly, that this was an argument they had often.

“What? You don’t want to sell to them as they pass through town? From what I hear, they are desperate for food.” Crescenio asked mockingly.

“If they had any money, I might consider it. But their paper money is no better than their word, and their coin long gone. And desperate men are dangerous men. Better to stay here.” Tio Pedro pulled back the cloth that covered the basket and chuckled with satisfaction. He pulled out a tortilla and ate it. When it was gone, he handed one each to Crescenio and Raul, then tossed a couple to the sheepherders, who had silently drifted down from their rock perches and were hovering nearby. Raul rolled his tortilla and nibbled on the end, his eyes darting between his uncle and his father as he appraised them both.

Tio Baca was one of the richest men in town, and his thoughts always centered on his money and how he could make more. He worried less about whether the Union or the Confederates could hold the little town of Socorro than he did about which side could pay the most for his goods. Raul’s father, on the other hand, had come from poor stock, and prized his pride more than money. He hated both the Northerners and the Southerners, and wanted both out of New Mexico. Raul sat between the two men, pulled first towards the argument of one and then the other.

The wind picked up at the opening of the box canyon, ruffling Zorro and Torro’s coats. Raul watched it swirl into a column of grass bits and dust. The hair on the back of his head rose. A tingle ran up his spine.

“It’s been a strange year. Extra cold this winter, but little snow. And now, diablos de polvo, this early,” Tio said. “Know what the Navajo call them? Chiindii. Spirits.”

Crescenio shivered and crossed himself. “Don’t go talking about spirits. Not with all the deaths we’ve had.”

Tio Baca laughed. “Surely you don’t believe in ghosts! They went the way of the Inquisition, and witches. We’re living in the age of science, now!”

“There are plenty of things left that your Galilleos can’t explain,” Crescenio said with a snarl.

Raul set his tortilla aside, unnerved by the argument. He didn’t want to think about ghosts, not with the faces of so many dead men haunting his dreams at night. Ever since the battle at Valverde Ford, he had found himself jerking up from his sleeping mat, gasping for breath like a drowning man, his heart pounding, his body soaked with sweat. The faces, blood smeared and broken, hovered over him long after he awakened, and he would find himself outside, staring at the stars as he tried to calm himself. But stars reminded him of the thousand Confederate fires he had seen while standing on the parapet at Fort Craig, and that memory would start his heart pounding once again.

Raul felt his heart pounding now as he got to his feet and left the argument behind him. Maybe his father was right, and the world of the dead existed here, beside his own. Maybe his uncle was right, and there were no such things as ghosts. The dead were just dead. He would have to side with one man or the other on this, as he would have to decide which was right on the question of foreigners in his land, and how he was to live his life. He loved and honored both men. How could he choose between them?

Zorro and Torro raised their heads and watched him pass between them with suspicious and hopeful eyes. When he was beyond the protection of the canyon, Raul sat on a boulder and stared at the immense land spread before him, the parallel lines of mountains and bosque snaking northward towards a distant horizon. The wind picked up again, whistling through the rocks and forming another dust devil. This one seemed to hover in front of him, shimmering and shifting until it almost coalesced into a figure of a young girl.

“Lupe?” His sister’s name slipped from his lips, half gasp and half prayer. Though barely audible, it seemed to have the strength to make the wind collapse on itself, dissolving into nothingness. Raul stared at the place where the shape had been, and saw, far in the distance, flashes of metal like a thousand falling stars amid a faint cloud of drifting dust. The time for indecisiveness was over.