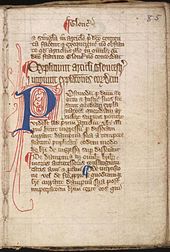

On June 15, 1215, in a place called Runnymede, King John signed the Magna Carta, the Latin name for the Great Charter that Daniel Hannan calls "the most important bargain in the history of the human race." Not only did the charter formalize the notion of freedom of an individual against the arbitrary authority of a despot, but it instituted a from of conciliar rule that was the progenitor of England's Parliament and America's Legislative Branch.

The Magna Carta was written by a group of rebellious barons who wanted to protect their rights and property from the overzealous taxation of the cash-poor King John. Before he was king, England's coffers were emptied by those seeking to ransom John's brother, Richard the Lionheart, who had been captured by a German prince on his way back to the Holy Land. Once crowned, John threw himself into battle with France in an attempt to regain the lands traditionally held by his family, the Angevins. John was not a good military leader, and suffered a series of staggering blows that resulted in the loss of all French lands for he English crown

When the defeated John returned from the Continent, he tried to rebuild his coffers by demanding scutage, a fee paid in lieu of military service, from the barons who had not joined him in war. The barons refused, and 40 joined in open rebellion. After they captured London, the barons forced John to meet with them at Runnymede and put his seal to the charter that protected their feudal rights.

Attribution: WyrdLight.com

Attribution: WyrdLight.com Its name comes from a combination of the Anglo-Saxon word 'runieg,' which means regular meeting, and 'mede,' which means meadow. During the time of Anglo-Saxon rule, from the 7th to 11th centuries, the Witan, or King's Council, met in the open air at Runnymede. It is not surprising, then, that John's Barons would choose this site to reassert their ancient rights and privileges.

For a translation of the Magna Carta in to English, click here.