"At their center was a fine looking man with silver hair that caught the morning sun and made him look as if a halo circled his head. He had a great, bushy mustache, sideburns, and sad, drooping eyes that made Jemmy feel as if this man had seen all the sorrow the world had to offer and had learned how to push through it. Jemmy instantly felt as if he could follow the man anywhere."

Many young men of the Confederacy were awestruck by Sibley. Many contemporary records attest to his natural charisma and ability to inspire people with his words.

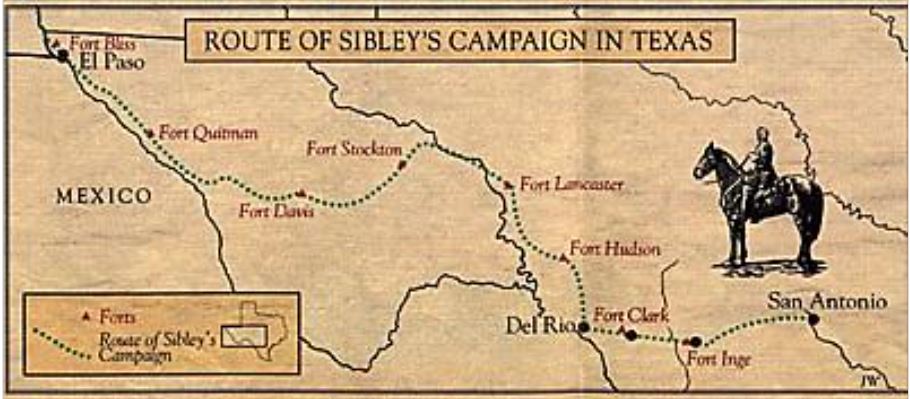

Sibley had just come back from talking Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederate States, into commissioning him as a brigadier general and authorizing him to recruit a brigade of volunteers in central and south Texas. Sibley’s plan was to march to El Paso, then occupy New Mexico, seize the rich mines of Colorado Territory, turn west through Salt Lake City, and capture the seaports of Los Angeles and San Diego and the California goldfields, all while living off the land. His battle cry, “On to San Francisco!” inspired 2,000 men to join his campaign. By early fall of 1861, Sibley had three regiments of what he named The Army of New Mexico, plus artillery and supply units, camped on the outskirts of San Antonio.

He was right to an extent on two of these three groups. Sibley was not the only Union soldier with ties to the south who had abandon their posts to join the south, and some did join Sibley's army. And particularly in the southern part of the state, which had seen an influx of settlers from Texas after the Gadsden Purchase, many citizens were Confederate sympathizers. However, most white settlers in the northern part of the state were allied with the North, and while most Hispanics and Indians didn’t like the Americans, they hated Texans even more. These people considered Sibley’s Army Texan, not Confederate. So with the exception of settlers in the southern part of the state, the citizens of New Mexico had no intention of supporting Sibley's troops.

Without the support of the local populace, Sibley had to rely of capturing supplies from the Union Army. This, too, proved more difficult than he had anticipated. Sibley was not able to capture Fort Craig and its supplies. By the time he arrived in Albuquerque, he found that the Union garrison had burned all its supplies before retreating north. What had escaped the fire had been squirreled away by a local population that wasn't inclined to share with an invading army.